Fertility in Ghana

Sources: Population Reference Bureau. (n.d.). PRB International Data. Population Reference Bureau International Data. Retrieved March 2, 2022, from https://www.prb.org/international/geography/northern-america/

United Nations. (n.d.). World Population Prospects . United Nations. Retrieved March 2, 2022, from https://population.un.org/wpp/...

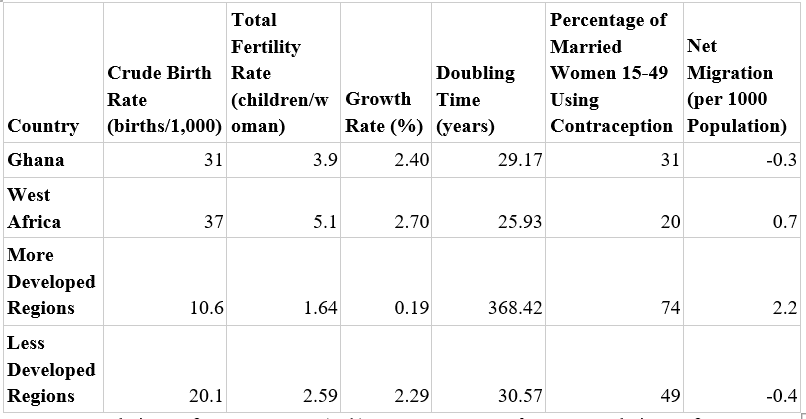

Birth Rate

Crude birth rate is a fertility measure that is calculated by determining the number of live births per 1,000 population per year. The crude birth rate in Ghana is 31, which is lower than the average in West Africa (37). However, Ghana’s crude birth rate is still higher than the average of less developed regions (20.1) and almost three times as high as the rate in more developed nations (10.6).

Total fertility rate is the average total number of children that would be born to a single woman in her lifetime if the current fertility trends are constant. It is calculated by adding the single year age specific rates during a particular year and is measured in children/women. Ghana’s total fertility rate is 3.9, which is considerably lower than the average of West African countries (5.1). However, this is a higher fertility rate than both less developed regions (2.59) and more developed regions (1.64).

Growth rate is the number of people added to or removed from a population each year due to births and net migration. It is calculated as a percentage of the population. Doubling time is the amount of time in years that if growth continues at the current rate, a country will double in size. It is calculated by dividing 70 by the growth rate. Ghana has a doubling time of 29.2 years, which is less than the average doubling time of more developed regions (368 years). Ghana’s doubling time is longer than in the average of other West African countries (25.9) but is relatively similar to the average doubling time in less developed regions (30.57)

Percentage of married women 15-49 using contraception is a measure that demonstrates the number of women choosing to alter their fertility. It is measured as a percentage of married women who are using any form of contraception. In Ghana 31% of women in this group were using contraception, which is considerably higher than the average of other West African countries (20%). Still, this is lower than the 49% of women using contraception in the average lower income country and 74% across high income countries.

All in all, Ghana has much higher fertility across all measures compared to more developed regions and slightly higher fertility across all measures compared to less developed regions. However, compared to other countries in Western Africa, Ghana has lower fertility across all measures.

Net migration is a measure of the change in population per 1000 people due to immigration or emigration. A positive net migration represents immigration to a country and a negative net migration indicates emigration from that country. Ghana's net migration rate was -.3 per 1,000 population, indicating that more people are emigrating from the country than immigrating to it. This is similar to the rate in the average of less developed nations (-.4). However, whereas more people are leaving Ghana, the average West African country has a net migration rate of .7, which indicates that there is net movement of people into the country. More developed regions have a net migration rate of 2.2 which indicates more people are immigrating to these regions than leaving them.

Trends

Source: Population Reference Bureau. (n.d.). PRB International Data. Population Reference Bureau International Data. Retrieved March 2, 2022, from https://www.prb.org/international/geography/northern-america/

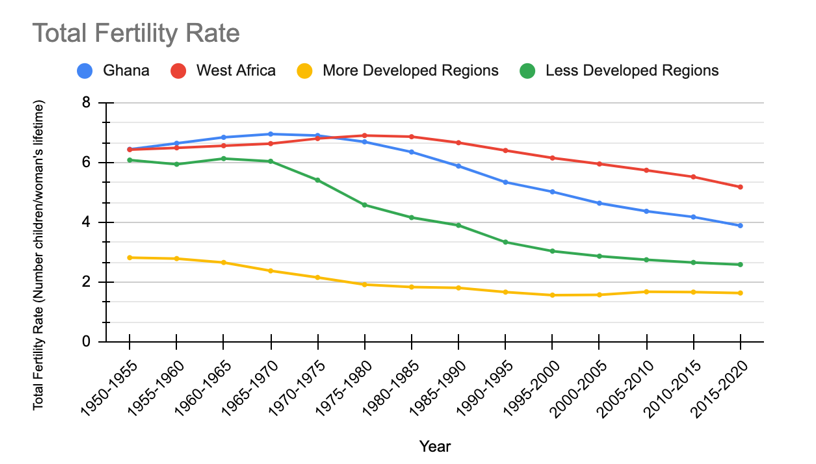

Ghana has had a similar decline in fertility compared to less developed countries. Ghana started with the same total fertility rate as the average of countries in West Africa (6.4), which was slightly higher than less developed nations (6.1) and much higher than more developed regions (2.8). In Ghana from 1950-1975 there was a small increase in the total fertility rate (peaking at 6.9) and this trend was also seen in Western Africa. During this time period, the fertility rate was relatively constant in less developed regions but was decreasing in more developed nations. From 1975 to present, the total fertility rate in Ghana has declined at a faster rate and by a larger amount than in all of Western Africa. Also important to note is that while Ghana’s fertility decline began in 1975, the decline in the rest of Western Africa did not begin until 1985. Currently, Ghana has a lower fertility rate than in Western Africa (3.89 and 5.18). Ghana’s fertility rate has declined by a smaller amount than the average of less developed nations (6.4 to 4 compared to 6.1 to 2.6). While the rate of fertility decline in Ghana was greater than in more developed regions, Ghana still has a higher fertility rate compared to the averages of less developed countries and more developed countries.

Interpretation:

Fertility decline in Ghana over the past four decades has been influenced by a variety of social and economic factors. Declining fertility has occurred across the globe, with the total fertility rate declining by 2 or more children per woman in many countries (Nykaro, 2021). A major driver of this change has been the effort to control population growth, especially in low income countries which are faced with food shortages, poverty, and overcrowding. High fertility is correlated with lower socioeconomic development and evidence suggests that controlling fertility allows a country to advance in other sectors (Nykaro, 2021). Specifically in Ghana, the government and outside organizations such as UNICEF have worked to hasten fertility decline as a means of promoting societal development.

Ghana stands out among West African countries in terms of its efforts and success in achieving fertility decline. Ghana has a comparatively strong health system and government as one of the first countries in Africa to achieve independence from British Colonization (Askew, 2015). Additionally, along with Kenya, it was the first country to establish policies to combat population growth in the 1960s (Askew, 2015). One avenue that the Ghanaian government and outside organizations have taken to combat high fertility rates is through the greater implementation of family planning services. Increasing the availability and quality of such services is correlated with a decline in total fertility rate (Banc & Grey, 2002). Family planning encompasses contraception which has been rapidly increasing in Ghana since the start of this policy, especially long acting forms such as intrauterine devices and injectables (Askew, 2015). Particularly after Ghana’s national population growth policy was revised in 1994 to include a greater emphasis on investment in family planning services, Ghana’s percentage of married women using contraception has increased (Askew, 2015). However, it is important to note that there is still an unmet need for contraception in Ghana. In fact, while the unmet need for contraception in Ghana has been declining, this rate of decline has slowed in recent years (Askew, 2015). This explains why although Ghana has experienced large declines in fertility rate, the nation has not reached fertility levels as low as the average of less developed nations.

Another intervention that has contributed to declining fertility in Ghana is the greater emphasis on investment in educating young girls. Studies have found that educational attainment is negatively associated with total fertility rate even after accounting for other confounding variables (Nykaro, 2021). The Ghanian government and organizations such as UNICEF attempt to support girls to stay in school and women to seek higher education. Higher educational attainment is hypothesized to lead to decreases in fertility in several ways. Education women are likely to have more knowledge about contraception use and are thus able to control their fertility to a greater degree (Nykaro, 2021). Additionally, women may intentionally postpone childbearing to pursue higher education or vocational advancement (Nykaro, 2021). Thus, programs that promote education of girls in Ghana have contributed to the declining fertility rates since the 1960s. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that fertility is negatively associated with the wealth status of a household (Nykaro, 2021). Education is expected to lead women into skilled labor force participation, which in turn reduces cumulative fertility [32], and that educated women are more likely to have knowledge about and access to contraception and use contraceptives more effectively [33]. However, highly educated women may also be likely to postpone childbirth because of a considerable part of their reproductive years they may spend in education. (Nykaro, 2021) Likewise, cumulative fertility is found to be negatively associated with the wealth status of the household (Nykaro, 2021). Therefore, Ghana’s economic advancement has contributed to declines in fertility seen over the past 40 years.

References

Askew, I., Maggwa, B., & Onyango, F. (2015). Fertility transitions in Kenya and Ghana: Trends, determinants and implications for policy and programs. Population and Development Review, 41(S1). https://doi.org/10.31899/rh4.1...

Blanc, A. K., & Grey, S. (2002). Greater than expected fertility decline in Ghana: Untangling a puzzle. Journal of Biosocial Science, 34(4), 475–495. https://doi.org/10.1017/s00219...

Nyarko, S. H. (2021). Socioeconomic determinants of cumulative fertility in Ghana. PLOS ONE, 16(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journa...

Population Reference Bureau. (n.d.). PRB International Data. Population Reference Bureau International Data. Retrieved March 2, 2022, from https://www.prb.org/internatio...

United Nations. (n.d.). World Population Prospects. United Nations. Retrieved March 2, 2022, from https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/

Post a comment