Maternal Mortality Disparities in Ghana: Explanations and Proposed Interventions

Most maternal deaths during pregnancy and childbirth are entirely preventable with prenatal healthcare and birth with a trained provider. Many countries have created a health system that prioritizes maternal health through evidence-based interventions, which has led to a dramatic decline in maternal mortality. Despite this progress, women are still dying at alarming rates in the poorest countries, evidenced by 50% of the world’s maternal mortality occurring in sub-Saharan Africa (Afulani, 2015b). Ghana is an outlier among sub-Saharan African countries as it is one of the wealthiest, has a health system that attempts to provide care for all citizens, and has a markedly lower rate of maternal mortality. However, the latest World Health Organization (WHO) statistic of 308 deaths per 100,000 live births in Ghana shows that the battle against maternal mortality is far from over (2017). Despite its efforts, the nation did not reach the Millennium Development Goal of a maternal mortality ratio below 190 in 2015 (Ameyaw et al., 2021). While the rate is still declining in Ghana, recent trends show the average annual rate of decline has been stalling (UNICEF, 2019). Still today, a Ghanian woman’s lifetime risk of dying as a result of a pregnancy is 1 in 82 (Afulani, 2015a). These trends are perplexing because more than 90% of Ghanaian women attend at least one antenatal care visit (PRB, 2015). Clearly, the widespread use of prenatal care in Ghana is insufficient to dramatically alter the maternal mortality rate. More recently, studies have determined how the more focused interventions of a greater quality of antenatal care and the use of skilled birth attendants have the potential to cause a more consequential decline in Ghana's maternal mortality.

Antenatal healthcare is essential to women in countless ways. These visits provide health education, screening, interventions, and preventative care for both a mother and child. Furthermore, the socioemotional support from a provider is associated with improved pregnancy outcomes (Afulani, 2015b). The WHO asserts that it is essential that women receive care at least four times during pregnancy and recommends that women should ideally seek eight prenatal care visits before delivery (Afulani, 2015b). Although 90% of Ghanaian women attend at least one appointment, only 80% complete four visits and even fewer attend at least eight (Afulani, 2015a). There is a problem of prenatal care attrition and a few visits are not enough to dramatically alter maternal mortality. Furthermore, even mothers who attend the most antenatal care visits may not be receiving the maximum benefit of all services, indicating that simply getting women to attend appointments is not enough. Data shows that only 25% of Ghanaians receive all WHO-defined essential antenatal care services (PRB, 2015). Additionally, many women self-report that the quality of care they receive is low, likely because they are not offered all services (Afulani, 2015a). Part of the slowing decline in maternal mortality in Ghana can be attributed to antenatal care dropout rates and poor quality services for those who do attend.

Another intervention proven to save maternal lives is the use of a skilled healthcare provider at childbirth because most maternal deaths occur during delivery (Afulani, 2015b). Skilled birth attendants (SBAs) have the knowledge and resources to intervene during an obstetrical emergency and save lives. Though SBAs may vary in expertise from physicians to midwives, the most important determinant of their success in saving women is that they know how to identify an emergency; from there they may subsequently treat or find someone who can (Afulani, 2015a). Skilled birth attendance implies care during labor and birth but also in the postal period. However, only 78.9% of Ghanian women deliver within the presence of an SBA and many choose to do so at home versus in the hospital setting (WHO, 2022). Studies have also found that the use of an SBA is positively associated with antenatal care use (Afulani, 2015a). It is hypothesized that antenatal care is an important avenue for educating women about their pregnancy and encouraging them to seek an SBA. The intersection between suboptimal use of prenatal care services and the many women delivering without an SBA is what is holding Ghana back from further improvements in maternal mortality.

An important distinction is that maternal mortality is unevenly distributed across Ghana and varies with demographic characteristics. It is well established that the poorest women in Ghana, particularly the uneducated living in rural areas, are at increased risk of dying during pregnancy and childbirth (PRB, 2015). Several factors mediate these disparities. For instance, women in rural areas are more likely to become teen mothers and tend to have more children than their urban counterparts, both of which are associated with increased maternal mortality (Ghana Health Service (GHS), 2018). Distance from a healthcare facility is also a deterrent to receiving care. The poorest communities in Ghana tend to be farther from health facilities and have limited access to transportation. In a study of the family homes of deceased mothers in Ghana, the average time to the nearest health facility was greater than 30 minutes. Many family members expressed difficulty accessing and affording transportation (GHS, 2018). The disparity in distance to care is an important contributor to the differential uptake of prenatal care by socioeconomic status in Ghana which leads to higher maternal mortality among the poor.

Additionally, economic barriers to care are especially challenging for poor women, which leads to lower healthcare utilization and thus higher mortality. Although Ghana has a national health insurance plan provided at a low cost, not everyone is enrolled. 79% of women in Ghana are registered, but coverage varies greatly; in the poorest regions, a mere 39% of people are enrolled (GHS, 2018). Generally, wealthy women are more likely to be enrolled in the national health insurance, leading to greater utilization. Furthermore, 45% of women report being asked to make payments at an antenatal care visit, even though this care is supposed to be free for enrolled women (GHS, 2018). In a national survey, 80% of women cited financial constraints as the main obstacle to seeking prenatal care (Barbi, et al, 2020).

Research has also demonstrated a direct relationship between socioeconomic status and the quality of antenatal care, with poor and uneducated women being at increased risk of receiving low-quality services (PRB, 2015). Further findings indicate that only 45% of the poorest Ghanian women received antenatal care rated as “good quality” compared to 76% of the wealthiest women (PRB, 2015). A similar disparity was found when women were grouped based on education level, meaning that the poorest women with no education received the worst quality care. This trend can be explained by the fact that poor women tend to obtain their prenatal care at lower-level health facilities which are more likely to provide poor quality care (PRB, 2015). A reason that lower-level health facilities deliver poorer care is that these areas have not been invested in; they are concentrated in regions to have less robust health infrastructure and fewer healthcare providers (Afulani, 2015b). While wealthy women have the means to seek high-quality care by traveling further distances and paying for access, poorer women may have no other option but to seek the care they can afford from the closest facility. As a result, wealthy women tend to receive antenatal care in government hospitals and private health facilities which provide higher quality services compared to the smaller clinics that are the only option for poorer women (Afulani, 2015b). Some authors even propose that poor women with no education are most vulnerable to suboptimal care because they may not be offered certain services when it is assumed that they will not be able to afford them (Afulani, 2015a).

Further, poor women are more likely to receive low-quality treatment no matter the setting in which they seek antenatal care (Afulani, 2015b). In a study of women’s perceptions of the antenatal healthcare system, poorer and uneducated women experienced greater experiences with unfriendly personnel, physical and verbal abuse, lack of privacy, and poor hygiene/sanitation, which led to a more negative view of the healthcare system (Barbi et al, 2020). Perceived quality of care is an important determinant of one’s future healthcare-seeking behavior; people who have negative experiences with healthcare providers are more likely to forgo additional treatment even when it is seen as necessary. Thus, the greater rate of negative experiences with the health system could account for the lower proportion of poorer women seeking antenatal care (Afulani, 2015a). A final determinant of substandard prenatal care among poorer women is that uneducated women may not know what services they should be receiving and thus do not ask for them (Afulani, 2015a). Women with higher education have more knowledge of reproductive health, abnormalities in pregnancy, and what services they should ask about. Poor women are unable to advocate for such services. In sum, there are a multitude of factors that contribute to the low perceived quality and poor utilization of prenatal care by poor women which contribute to the disparities in maternal mortality.

Another trend that contributes to higher maternal mortality among poorer women in Ghana is that they are least likely to deliver in the hospital setting or with an SBA. One study found that while 95% of the richest women delivered with a skilled birth attendant, only 24% of the poorest women did (Afulani, 2015b). This stark disparity means that birth is a far more dangerous experience for poor women and as a result, they are more likely to die during delivery. In a nationwide study, most women across Ghana acknowledged the importance of antenatal care and were aware of the benefits of hospital delivery (Barbi et al, 2020). However, health facility deliveries are highest in the wealthier Greater Accra region and lowest in the poorer Northern region of Ghana (Ghana Health Service, 2018). This may be explained by the fact that poor women are often not able to afford an SBA and may have difficulty even finding one in their area. Negative perceptions of healthcare are a deterrent to seeking SBAs, which aligns with the trend that poorer, uneducated women have worse experiences with the healthcare system (Afulani, 2015b).

Cultural norms are another factor affecting a woman’s decision to give birth in a hospital or with an SBA. Many women who sought skilled care reported that they were not the ones who initiated it, rather a mother or elder maternal figure did (Barbi et al, 2020). Poor women report receiving little support from their partners when they expressed the desire for an attended birth and others express strong adherence to the cultural value that the male has a responsibility of overseeing the birth in the home setting. Some were even discouraged by their male partners from seeking formal care during birth, even during emergencies (Barbi et al, 2020). These barriers women face in making decisions about their reproductive healthcare reveal that they are not empowered to make their own decisions. This may help explain the socioeconomic disparities of lower SBA births but higher maternal mortality rates given that poorer women are even less likely to advocate for themselves.

A Comparative Perspective

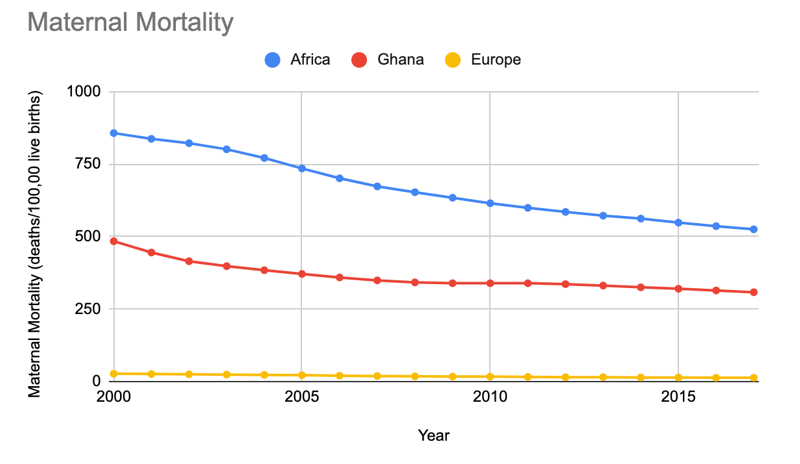

As previously stated, Ghana is an outlier among Sub-Saharan African countries in terms of maternal mortality, but it has a significantly higher rate compared to other regions, such as Europe (Figure 1). Maternal mortality has been lower in Ghana than its counterparts in Africa for many years, however, the gap has widened as the continent as a whole has experienced a more substantial decline in maternal mortality compared to Ghana. Over the past 15 years, the maternal mortality rate in Ghana has plateaued while the rate in Africa has declined more significantly. Today, at 308 deaths/100,000 births, Ghana remains centrally positioned between Africa’s average of 525 and Europe’s 13 (PRB, 2015).

In higher-income regions, such as Europe, the leading cause of maternal mortality is hypertensive disorders (Der et al., 2013). However, in Ghana and other low/middle income countries, hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal death (Der et al., 2013). The higher fraction of deaths due to hemorrhage in Ghana may be explained by the frequent blood shortages, frequent lack of running water and power, and lower number of healthcare workers per capita (Der et al., 2013). These factors are also more significant in rural communities among poor women, contributing again to the greater number of maternal deaths in this group. Furthermore, 86% of maternal deaths in Ghana due to hemorrhage occurred in the community rather than in a healthcare facility (Der et al., 2013). This demonstrates the difficulty of obtaining emergency obstetrical care in Ghana in stark contrast to higher-income regions where women have more ready access to hospitals for treatment of hemorrhage.

Because of the higher rates of maternal mortality, there is a much more significant burden on Ghana than in other countries. Besides the devastating cost to society that results from the loss of a woman to pregnancy and childbirth, there are high economic costs of maternal mortality. The families of deceased women may incur catastrophic healthcare expenses, which can not only devastate them but place a significant burden on the healthcare system. There are no estimates of the economic burden of maternal mortality in Ghana, estimates of the impact on the US are in the tens of billions of dollars even with a fraction of the mortality (WHO, 2017). While Ghana has made immense progress in decreasing maternal mortality across its history, it is still a tremendous problem for the country today.

Current Interventions

Despite the effort, Ghana's response to the high maternal mortality has fallen short. The government made significant investments in healthcare over the past 30 years, such as the creation of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in 2004 to pay for basic health services for all (Barbi et al, 2020). In 2007, it was expanded to give all women access to maternal and child health services without out-of-pocket payment (Ameyaw et al., 2021). These interventions have been successful in getting the majority of Ghanaian women to attend at least one antenatal care appointment, but the subsequent improvements in maternal mortality have not been as robust as expected (Afulani, 2015b). Clearly, more needs to be done than increasing the proportion of women using services, because this alone does not modify the structural barriers preventing women from utilizing antenatal care to the fullest extent.

The implementation of the NHIS has been slow, and many women are still asked by providers to pay some cost for their antenatal care (Afulani, 2015b). This is likely a cause of the high attrition rate of antenatal care seen in Ghana. Although the Community-based Health Planning Services was introduced in 2008 to target healthcare in rural locations, the maternal mortality disparities between the rich in the urban setting and the poor in rural settings persist (Ameyaw et al., 2021). Additionally, these programs fail to achieve their goals as they focus on making care available to all women but do not focus on the quality of the services they are providing. The unresolved discrepancy in the quality of care between the rich, highly educated and the poor uneducated women of Ghana remains and has kept maternal mortality high.

Policy Recommendations

Ghana’s approach to maternal mortality has its limitations and how it fails should be the target of future interventions to improve maternal health outcomes. First, high-quality antenatal care must be promoted in the underserved regions of the country. Continued antenatal care throughout pregnancy is the best opportunity to provide women with preventative and diagnostic measures that will ensure they have a healthy pregnancy (Afulani, 2015b). Funding is necessary to elevate the level of care that can be provided in lower-level health facilities where the majority of poor women are receiving care in Ghana (PRB, 2015). Such investment will allow providers to access the essential equipment and medical supplies needed to provide high-quality care. Additionally, a higher standard of care should be established to ensure that women across the country are given the same prenatal health benefits. Core interventions that must be standardized include sexually transmitted infection testing, vitamin supplementation, malaria treatment, HIV treatment, and blood pressure monitoring (PRB, 2015). The government can accomplish these goals by providing funding to train more healthcare workers and providing incentives to retain qualified practitioners in lower-level facilities (PRB, 2015). These measures will not only promote better care that will detect and treat pregnancy problems early but will ensure women have a positive experience that will promote their return for future services. By targeting the quality of the lower-level health facilities that poorer women utilize, maternal survival rates can be improved in poorer women.

The second intervention that will be most successful in decreasing maternal mortality in Ghana is to increase the proportion of poor women using an SBA. The WHO identifies SBAs as the “single most critical intervention” to reduce maternal mortality (Afulani, 2015a). Since the use of SBAs is lowest in the poor, uneducated women in Ghana, the government should specifically target interventions promoting SBA use in these populations. One route to improve the rate of SBAs among the most disadvantaged in Ghana is to address the lack of skilled providers in poorer areas by training SBAs with a standardized curriculum and ensuring that they are easily accessible to all. This may be accomplished by increasing the incentive to work in lower-level health facilities and bridging the gap between facilities and families using community healthcare workers.

There is a vital link between the quality of antenatal care and the use of an SBA. Ghanian women who perceive the antenatal care they receive as high quality are twice as likely to use an SBA as those who rate their experience poorly (Afulani, 2015a). These trends may be mediated by the fact that women who have positive experiences with a health system are more likely to return for follow-up appointments then have an attended delivery. Thus, to decrease maternal mortality by maximizing the number of women using SBAs, the health system must ensure that women have frequent visits with a prenatal provider and they are satisfied with the care they receive. Providers should be trained to be friendly and nonjudgmental, as well as competent. They should guide women towards interventions that will save their lives, such as the use of an SBA. With these interventions specifically targeting those at the highest risk, Ghana has the potential to make marked improvements in its maternal mortality rate.

References

Afulani, P. A. (2015a). Determinants of maternal health and health-seeking behavior in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of quality of care. UCLA. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1pt4h3zh

Afulani, P. A. (2015b). Rural/Urban and Socioeconomic Differentials in Quality of Antenatal Care in Ghana. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117996

Ameyaw, K. E., Table, A., Kissah-Korsah, K., & Amo-Adjei, J. (2016). Women’s Health Decision-Making Autonomy and Skilled Birth Attendance in Ghana. International Journal of Reproductive Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6569514

Ameyaw, E. K., Dickson, K. S., & Adde, K. S. (2021). Are Ghanaian women meeting the WHO recommended maternal healthcare (MCH) utilization? Evidence from a national survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(161). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03643-6

Barbi, L., Cham, M., Ame-Bruce, E., & Lazzerini, M. (2020). Socio-cultural factors influencing the decision of women to seek care during pregnancy and delivery: A qualitative study in South Tongu District, Ghana. Global Public Health, 532-545. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1839926

Der, E. M., Moyer, C., Gyasi, R. K., Akosa, A. B., Tettey, Y., Akakpo, P. K., . . . Anim, J. T. (2013). Pregnancy Related Causes of Deaths in Ghana: A 5-Year Retrospective Study. Ghana Medical Journal, 47(4), 158-163. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3961851/

Ghana Health Service & Ghana Statistical Service. (2018). 2017 Ghana Maternal Health Survey. https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR251/SR251.pdf

Public Reference Bureau. (2015). Improve Antenatal Care in Ghana's Lower-Level Health Facilities https://www.prb.org/resources/improve-antenatal-care-in-ghanas-lower-level-health-facilities

UNICEF. (2019). Trends In Maternal Mortality. https://data.unicef.org/resources/trends-maternal-mortality-2000-2017/

World Health Organization. (2022). Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births) https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/maternal-mortality-ratio-(per-100-000-live-births)

Appendix A

Figure 1: A comparison between the maternal mortality ratio in Africa, Ghana, and Europe from 2000 to 2017.

Post a comment