Qualitative Study: Graduate Student's Use of AI

Research Question

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has experienced a surge in popularity over the past few years, and it has the potential for a multitude of uses in coursework and research. However, there is a paucity of literature investigating how graduate students are adapting to this novel technology. Therefore, this study aims to understand how AI is impacting graduate students and how they feel about it. The main research question addressed in this paper is “In what ways are graduate students using AI?”

Methods

This was a group project conducted in collaboration with five other graduate students as part of a qualitative methods course. The research topic was selected based on a group discussion. Together, we developed and revised an interview guide. Participants were selected via convenience sampling; half of the participants were members of the qualitative methods class, and the rest of the interviewees were other graduate students known to the individuals in the research group. All interviews were conducted by individual researchers in the group. We completed half of the interviews before coming together as a group to revise the interview guide. The newly revised interview guide was then used to interview the remaining participants. All interviews were recorded via the voice recording app on an iPhone, and transcripts were generated using OtterAi, then manually edited for accuracy. Reflexive memos were written independently to reflect on our experiences and feelings and how they may have affected data collection. Additionally, theoretical memos were written throughout the interview process to formulate ideas about patterns developing in the data.

Data analysis was conducted with the assistance of Dedoose. First, all members of the group open/initial coded three interviews using an in vivo approach, attempting to use the words of the participants to generate as many codes as necessary to best encapsulate the data. Then, all researchers developed a list of focus codes independently. Next, we came together to define a list of focus codes and their descriptions that we collectively agreed were comprehensive of the data. We individually focus-coded half of the interviews in Dedoose with the list of codes we developed before coming together to revise the code list and definitions based on our use of the codes thus far. No codes were modified, added, or removed during this process. Finally, we independently coded the remaining interviews. After focus coding, four single-code memos were written, and two integrative memos combined multiple codes to draw comparisons between the themes appearing in the data.

Findings

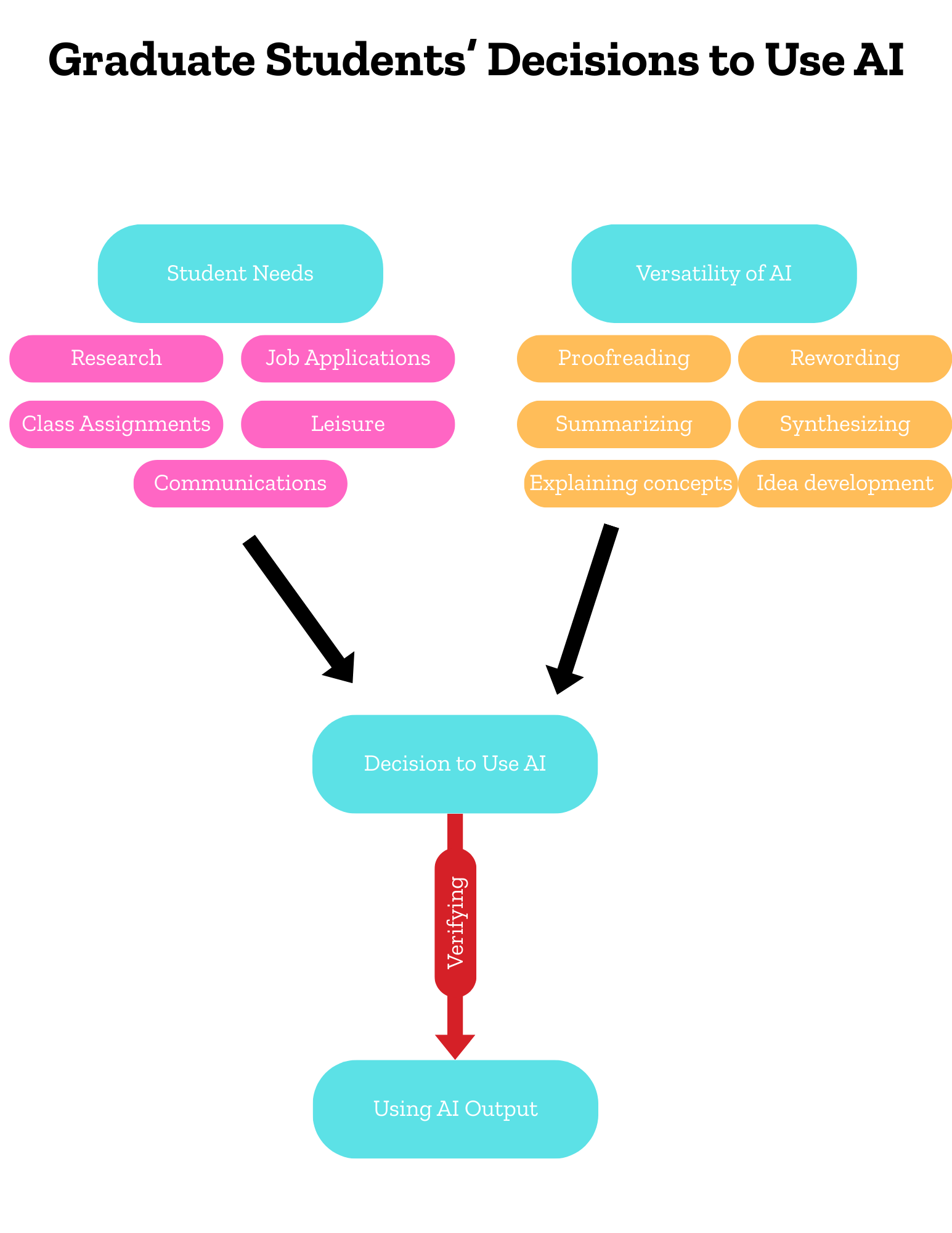

Graduate students in this study reported using AI in various ways, and they often commented on the versatility of the programs they used. They described a myriad of ways that they use AI in their coursework, research, and leisure activities to fulfill their needs; they use AI for developing ideas, explaining concepts, summarizing information, synthesizing information, checking homework assignments, writing emails, finding information, and generating practice questions and examinations. However, the most common way that graduate students in this study used AI was editing their written work through two processes, proofreading and rewording.

The first of these uses, proofreading, encompasses checking spelling and other “simple grammatical things like adding a comma,” said one 26–30-year-old female master’s student. Interviewees found AI to be a helpful supplement to existing grammar and spell-checkers they have used in the past, like Grammarly. Some of the students used AI in this way as a supplement to their concurrent use of other these other spell-checkers and grammar checkers. Others have found AI to be superior to these programs and thus a replacement for them. For instance, a 26–30-year-old male doctoral student described AI proofreading as superior, “like Google Docs and Microsoft Word have some level of being able to catch text errors, but certainly not as efficient.” In sum, students are using AI to proofread their assignments and research work, either using it to fill in the gaps of what other spell-check applications missed or as a replacement for traditional spell checks because AI is more efficient at proofreading.

Beyond spell-check and grammar editing, participants described a “perk” of AI being that it allows them to clean up what they are writing beyond writing convention errors—referred to as rewording. Multiple participants described using AI extensively to reword something that they have written, going beyond fixing spelling and grammatical errors to “rewrite” or “paraphrase” their work. For instance, a 20–25-year-old female doctoral student emphasized her use of AI for paraphrasing, saying, “So I'll throw it in there to kind of paraphrase it or like shuffle it up to make it better or like clean it up.” Similarly, another 20–25-year-old female doctoral student said she uses AI frequently “to paraphrase or rephrase what I'm thinking, and make sure my sentence structure is there.” Our graduate students also tended to use AI to paraphrase something that they were writing if it just wasn’t coming out the way that they envisioned. It often helps them identify “something that’s missing” in their writing that they cannot “figure out what it is.”

These two themes of AI use—proofreading and rewording—demonstrate how graduate students are using AI in ways similar to how they use other programs, but they are also using it in novel ways that they are unable to do with other programs. With proofreading, students had nothing but positive things to say about AI; they felt that it was more efficient at correcting their work than spell-check or Grammarly. However, with rewording, though many students found it helpful, some did note that there were limitations and drawbacks. Students noted that they had to remain active in choosing which parts of the reworded output they wanted to keep because the way that AI rewords something may not coincide with what they wanted to say or how they wanted to say it. One participant found that she had to be selective about choosing to use AI output to reword her work because her personal voice was often lost in the translation. Perhaps students are more accepting of AI when it comes to using it to replace functions that they already use technology for, like proofreading, but they are more cautious of using it in novel ways that they feel may infringe upon their creative voice.

Despite the multitude of ways in which the graduate student interview discussed using AI, there was clear evidence that students do not take AI output at face value. Most interviewees discussed how they always needed to verify, validate, or cross-check information they obtained from AI, and this was one of the most commonly discussed drawbacks of using this technology, as reported by the participants. They tended to be cautious about taking the information they receive from AI as 100% accurate because they had experience receiving incorrect information from these programs before. A 20–25-year-old female doctoral student said that AI output is “kind of like sketchy.” Another 20–25-year-old female doctoral student said, “I have noticed that sometimes it's wrong… it’ll quite frequently give me incorrect answers…obviously not everything is correct in there.” Due to this skepticism, participants often verified or supplemented the content given to them by ChatGPT with information retrieved from what they believed were more reliable search engines: “I'll like go into Google and see like other real resources that I can cite in my assignments and stuff” said a 20–25-year-old female doctoral student. Additionally, several interviewees described having to verify the citations given by ChatGPT, feeling a personal responsibility to ensure that evidence was not only cited correctly but also not misconstrued.

Integrating AI into graduate student life has many potential benefits; it helps students increase the quality of their work, allows them to produce more work efficiently, and accomplish tasks in creative ways. However, it is important to note that access to these benefits is not universally guaranteed. Many AI programs exist behind a paywall; they either limit the amount of free output one can generate in a day, or free versions rely on older, less accurate models. Thus, people who cannot afford this expense may suffer as those around them benefit from using AI. This may exacerbate disparities between those who are able to pursue higher education and those who do not have access to the tools that would give them an advantage. One interviewee, an international doctoral student, described how purchasing AI permissions would be out of reach for people in his home country: “I don't think a lot of people in those high schools or elementary schools can afford this just yet, even for $20 a month. But if it does get cheaper, it, to me, feels like a great equalizer in that sense.” This suggests that if AI continues to be reserved for the most privileged, it may exacerbate disparities in education and achievement; however, if AI is made available to everyone, it may promote equity in education.

Conceptual Map

Post a comment