Research Proposal: An Assessment of Climate Change and Health Education Among US Medical Schools

Introduction

The environment has an incredible and wide-ranging impact on human health, as evidenced by the estimation that one in four global deaths can be linked to environmental conditions (Prüss-Ustün et al., 2016). In the past ten years, there has been growing recognition of the threat of climate change to health. The World Health Organization has since identified climate change as the "greatest threat to global health in the twenty-first century" (WHO, 2015). Physicians are an important stakeholder group with a vested interest in this issue as they treat patients affected by the health consequences of climate change. Furthermore, doctors can play a crucial role in advocating for policies that mitigate climate change and its range of effects that impact health (Kreslake et al., 2018). Despite doctors holding a position of power to advocate for such change, environmental health is not a standard part of the medical school curriculum (Hampshire et al., 2021).

Furthermore, instruction on climate change in medical school is notably understudied, making it difficult to evaluate these curricula. This knowledge gap ultimately leaves future healthcare leaders ill-equipped to address one of the greatest threats to human health. Understanding how climate change's impact on health is currently communicated in medical education is a necessary first step to developing a more comprehensive curriculum that prepares emerging physicians to meaningfully engage with these issues in their future practice. This proposed study attempts to fill this gap by better characterizing the state of climate change and health education in US medical schools and exploring the content covered and pedagogical strategies that are used.

Literature Review

Climate Change and Health

Climate change negatively impacts health in a myriad of ways, from leading to unintentional injuries, increased spread of communicable diseases, and exacerbation of chronic conditions. For instance, it is well established that climate change increases the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and heat waves, which can cause death among those who are most vulnerable (CDC, 2024). Climate change impacts patterns of infectious disease spread, as insect vectors follow weather changes and flooding contaminates drinking water sources (CDC, 2024). Additionally, greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution contribute to chronic respiratory and cardiovascular conditions and various types of cancer (CDC, 2024).

As global temperatures continue to rise, the impact of climate change on health will become even more concerning. The World Health Organization predicts that there will be an estimated additional 250,000 deaths annually attributable to climate change by 2030 (WHO, 2025). Additionally, the disproportionate impact of climate change on low-income countries will exacerbate the already rising disease burden that disproportionately affects disadvantaged groups (CDC, 2024). Climate change is undoubtedly a global crisis that threatens the health and well-being of billions of people. Role of Health Professionals in Climate Change

Health professionals can play a pivotal role in addressing climate change and its impact on health in several ways. First, physicians are facing the task of treating the health issues caused or exacerbated by climate change. Beyond the doctor's office, physicians can advocate for solutions that prevent or mitigate climate change. The idea that health professionals have a responsibility to be informed about climate change and advocate for solutions is not a new concept; Jameton (2017) recalls, in the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, that health professionals have been actively involved in climate change advocacy since 1989. Since then, a growing number of physicians, intergovernmental organizations, and health associations have endorsed medical professionals' responsibility to combat the climate change crisis (Wellbery et al., 2018).

Some argue that doctors are uniquely positioned to advocate for climate change solutions because they are "frontline witnesses to the human toll of climate change" (Kreslake et al., 2018). Additionally, doctors are members of a well-respected profession, and this privileged position often gives them the power of influence in their communities. These calls to action range from actions doctors take in their own homes to ways they can influence climate-protective legislation. For instance, Spiby et al. (2008) urge doctors to inform themselves about climate change, use less energy, and to "put climate change on the agenda of all meetings." Doctors can address climate change by serving as models for sustainability practices, informing society about the health effects of climate change, and helping patients adopt strategies to reduce the health risks of climate change at the individual level (Bugaj et al., 2020). Jameton (2017) calls on doctors to lobby for international, national, and regional policies to mitigate climate change and its health effects, especially in the face of political denial of climate change. Hughes (2024) recalls that physicians have encouraged systemic changes in many other public health crises through activism, and climate change should be no different. As members of one of the most trusted professions in society, doctors have the power to advocate for climate protection campaigns.

Students’ Existing Knowledge

For doctors to effectively intervene on climate change's health effects at the individual and community level and advocate for mitigation policies, they must be well informed about the issue. Additionally, they need to feel well-equipped to be leaders in climate change advocacy. Thus, preparing and motivating future physician leaders-- today's medical students-- to take on this role is essential. Understanding how this instruction is currently integrated into medical education is a necessary first step to better prepare physicians to confront the challenges posed by climate change in their future careers. Yet, there is limited data on medical students' knowledge of and attitudes toward climate change and health. Understanding future medical leaders' knowledge base and attitudes about this subject will help educators better prepare them to confront the challenges posed by climate change in their future careers.

A few US and international studies examine medical students' baseline knowledge of climate change and their preparedness to address the health consequences of climate change and advocate for solutions. In one study of medical students in Pakistan, most participants believed in the anthropogenic cause of climate change and could name specific ways that climate change impacts health, including air and water quality-related illnesses, extreme weather, flooding-related displacement, and mental health distress (Shariff et al., 2024). Another study in Iran found that medical students understand the significant impact that climate change has on health through environmental degradation and climate-related disasters (Heydari et al., 2023). Other studies take this analysis further, testing not only medical students' knowledge of climate change but also their understanding of potential ways to address the crisis. A study by Pandve & Raut (2011) in India demonstrated that while medical students tend to be well aware of the health hazards that climate change poses, they knew less about potential mitigation strategies.

While some evidence demonstrates that medical students are aware of the health consequences of climate change, less is known about whether medical students feel an individual and professional responsibility to address these consequences. Understanding how medical students see their role in addressing climate change's health effects will be essential in developing curricular experiences that motivate future physicians to be climate advocates. Bugaj et al. (2021) compared German medical students' understanding of climate change and its health consequences with their perceived responsibility as future physicians to address this health threat. Though they found that students were generally well informed about the consequences of climate change that affect human health, this knowledge did not necessarily translate into a sense of professional obligation to take on an active role in educating patients and society (Bugaj et al., 2021). Additionally, while most students recognized that as future physicians, they would be social role models for climate-protective behaviors, fewer felt obligated to educate patients on climate change and its health consequences (Bugaj et al., 2021). A study by Boland & Temte (2019) of recently graduated US doctors investigated students' attitudes towards a physician's role in climate change and health advocacy. While most students agreed that, as physicians, they would function as role models for others, few agreed that they had a social responsibility to take direct action against climate change through advocacy (Boland & Temte, 2019). Taken together, this data demonstrates the inadequacy of existing climate change curricula not in informing students but in increasing their sense of responsibility for climate change advocacy. Climate Change Communication in Medical School

Climate change and its health impacts are not a traditional component of the medical curriculum, and these curricula have not kept pace with the growing consensus that this should be incorporated into medical students' learning (Wellbery et al., 2018). There is limited data on exactly how many medical schools have climate change and health instruction, but the available evidence suggests that not many do. For instance, a recent survey of international medical schools found that just 14.7 percent integrated climate change and health into any of the four years of medical instruction (Omrani et al., 2020). There is no comprehensive survey that examines the presence of climate change and health education in US medical schools, but again, the inclusion of this curriculum seems to be an exception rather than the rule. Schools with climate change and health components in their curricula for which data is available include the Georgetown, Mount Sinai, Hackensack Meridian, University of California at San Francisco, Harvard, Emory, and Florida International University Schools of Medicine (Hu & Yang, 2023; Kligler et al., 2021; Marill et al., 2020; Omrani et al., 2020; Wellbery et al, 2018). These programs offer a variety of types of climate change and health instruction, ranging from single lectures, integrated modules, projects, and elective courses.

There is also a lack of assessment of the quality of medical school climate change and health instruction. One study involving 600 medical students from 12 US schools demonstrated that while students were objectively knowledgeable about the health effects of climate change, only 6.3% felt that their education prepared them to discuss the effects of climate change on health with their patients (Hampshire et al., 2021). Many students in this survey reported the desire for advocacy training, which was missing from their education. These results indicate that there is a discrepancy between what is being taught and what students need to prepare them for using their knowledge. The Planetary Health Report Card (PHRC) is an analysis of the planetary health curriculum of participating medical schools around the world, and part of this analysis includes an investigation of the quality of climate change instruction. The initiative's latest analysis demonstrated a general inadequacy of these curricula in the US, with only five schools receiving a curriculum score in the "A" range (PHRC, 2025). While this assessment is not limited to an analysis of a school's climate change curriculum, climate change is a component of the assessment that generates the grade. Apart from the schools that voluntarily commit to this project, there is insufficient data on the quality of climate change and health curricula in the US.

Effective Climate Change Pedagogy

Prior research illuminates the characteristics of effective climate change pedagogy outside of medicine. A systematic review by Monroe et al. (2019) identified the strategies used in 49 high school and university climate change education programs that increased their likelihood of achieving their outcomes. The authors characterized these into six themes for effective environmental education interventions. These included focusing on making the climate change information presented personally relevant or meaningful, creating activities that were designed to engage learners, using deliberative discussion to aid students in understanding their own and others’ views, giving the opportunity to interact with scientists and engage in the scientific process, specifically addressing misconceptions about climate change, and designing and implementing projects to address climate change (Monroe et al., 2019). Programs that used two or more of these pedagogical tools saw greater success.

The aforementioned Planetary Health Report Card (PHRC) identifies several components of effective medical school climate change curricula, specifically, which are components of their assessment of the adequacy of planetary health curricula. These include whether the instruction incorporates information on the relationship between various events impacted by climate change and health outcomes, including heat-related illness, infectious diseases, respiratory and cardiovascular conditions, and mental health events (PHRC, 2025). Furthermore, aspects of the PHRC that pertain to effective climate change and health curricula include an assessment of whether a school teaches medical students about the outsized impact of climate change on the health marginalized populations, and whether they include training that prepares future physicians for discussing the health effects of climate change with patients (PHRC, 2025). Unfortunately, the planetary health curricula report card cannot be used to solely grade the quality of climate change instruction in medical schools, as this measure also assesses the adequacy of environmental health instruction unrelated to climate change. Apart from these few components of the PHRC, there is no standardized way of evaluating climate change and health curricula in medical schools.

Gap

Despite the growing recognition that it is necessary to educate future physicians on the health impacts of climate change, there is a lack of a comprehensive assessment of the quality of US medical schools’ climate change instruction using effective methods of climate change pedagogy. Understanding the current state of climate change and health medical school education is essential to determining the gaps that must be addressed to better prepare physicians for important climate change work. Thus, this proposed study will attempt to fill this gap by surveying US medical schools and assessing the quality of their climate change and health curricula. This needs assessment will provide insight into designing future curricula that empower emerging physicians with the education they need to address the health consequences of climate change and advocate for solutions.

Research Questions

The purpose of this study is to examine climate change health curricula in US medical schools, including the content and methods of instruction, to identify gaps in the education of future physicians. The understanding gained from this study will provide insight into designing future curricula to empower emerging physicians with the knowledge they need to address climate change health consequences and advocate for solutions. The main research question is, “What is the state of climate change health education in medical school curricula?” This question encapsulates the following sub-questions:

RQ1a: How comprehensive is the content covered in medical school climate change health curricula?

RQ1b: Which elements of effective climate change pedagogy are used in medical school climate change health instruction?

RQ1c: What characteristics of medical schools are associated with stronger climate change health curricula?

Proposed Plan of Analysis

This study proposal aims to conduct a descriptive content analysis of US medical school curricula to investigate how various institutions incorporate instruction on the effects of climate change on health into their medical education. Data collection and analysis will be conducted at the medical school level by analyzing the content and methods schools use to educate about climate change.

Data Collection

Medical school climate change and health curricula will be assessed with a survey and a content analysis of the instructional materials. An electronic questionnaire be developed in Qualtrics to collect the following information from the US medical school administration: whether they address climate change in the curriculum; whether there is a dedicated course or lecture for climate change and health; which teaching methods are used (lecture, discussion, group activity, or mixed methods); where this climate change is incorporated into the curriculum (pre-clinical phase, primary clinical phase, advanced clinical phase, or longitudinally); and whether the instruction is mandatory, an elective, and/or an extracurricular event. Additionally, data from the US World News Reports will be gathered, including the following characteristics of responding each school: region, state, setting (suburban/urban/rural), size, whether it ranks in the top 20 medical schools, whether the school is MD or DO, and whether the school is private or public.

The questionnaire will be emailed to the administrative contact of the dean's office of each of the 154 MD schools and 41 DO schools in the US, with the aim of obtaining responses from at least 100 schools. In addition to filling out the questionnaire, participating schools will be required to send a copy of any climate change curricula materials, including but not limited to PowerPoints, activities, and quizzes. All school-level data will be anonymized, and individual school scores will not be shared. This encourages schools to participate without fear of a negative evaluation affecting their reputation. This will be done because a limitation of the PHRC (2025) is that medical schools are disincentivized to participate because data on their curricula is published in a report. Medical school administrators may be hesitant to have this evaluation publicized because a negative score could impact their enrollment. Thus, we will report data based on school characteristics to ensure the results of the assessment are confidential. While the scores of individual schools will not be published, we will report, for example, the average score for schools in a specific region or state.

Members of the research team will analyze the curricula with a standardized rubric that assesses the content and methods of instruction. The data collected from the school questionnaire and the analysis of the curricular materials will be used to develop three scores for each school: a content score, a pedagogy score, and a combined score.

Content Score

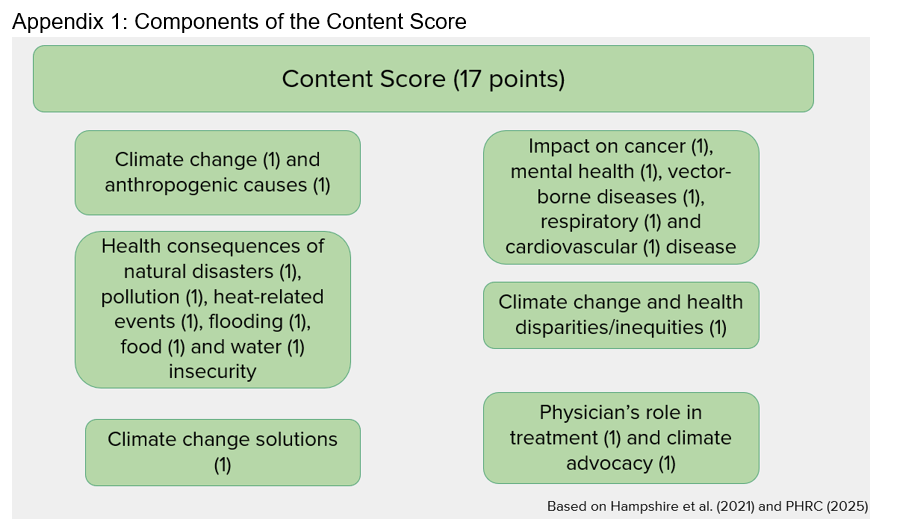

The content score will be calculated based on whether schools address the following topics in their curriculum, which were selected based on the survey of medical school curricula Hampshire et al. (2021) and the PHRC (2025). Points will be awarded for each of the following components: defining climate change (1) and its anthropogenic causes (1); conveying the health consequences of natural disasters (1), pollution (1), heat-related events (1), flooding (1), food (1) and water (1) insecurity; addressing the impact of climate change on cancer (1), mental health conditions (1), vector-borne infectious diseases (1) and chronic respiratory (1) and cardiovascular conditions (1); acknowledging climate change’s contribution to health disparities (1); emphasizing climate change solutions (1) and the physician’s role in treatment of climate change related health conditions (1) and in climate advocacy (1). Content scores will be calculated with a maximum of 17 points, with higher content scores indicating a more comprehensive climate change and health curriculum.

Pedagogy Score

Using the elements of successful climate change pedagogy as outlined in the systematic review by Monroe et al. (2019) and parts of the planetary the curriculum quality metric in the PHRC (2025), a pedagogy score for each school compiled based on whether the curriculum uses each of these strategies: attempting to make climate change information personally relevant(1), addresses misconceptions about climate change(1), uses activities designed to engage learners(1), uses deliberative discussion to aid understanding (1), provides opportunity to interact with climate change scientists (1), requires discussion of solutions to climate change (1), whether the instruction is a mandatory requirement (1) (as opposed to an elective or extracurricular event), whether there is a dedicated course or module (1), whether mixed teaching methods are used (lecture, discussion, activities, quizzes), and whether the instruction is longitudinal in the curriculum (1) (compared to a single instance). Pedagogy scores will be calculated with a maximum of 10 points, with higher scores indicating the use of more robust climate change instruction and communication methods.

Total Score

The content score, out of the 17 potential points, and pedagogy score, out of 10 potential points, for each school will be added together to produce a total score out of 27 points. Higher total scores will indicate a higher quality climate change and health curriculum.

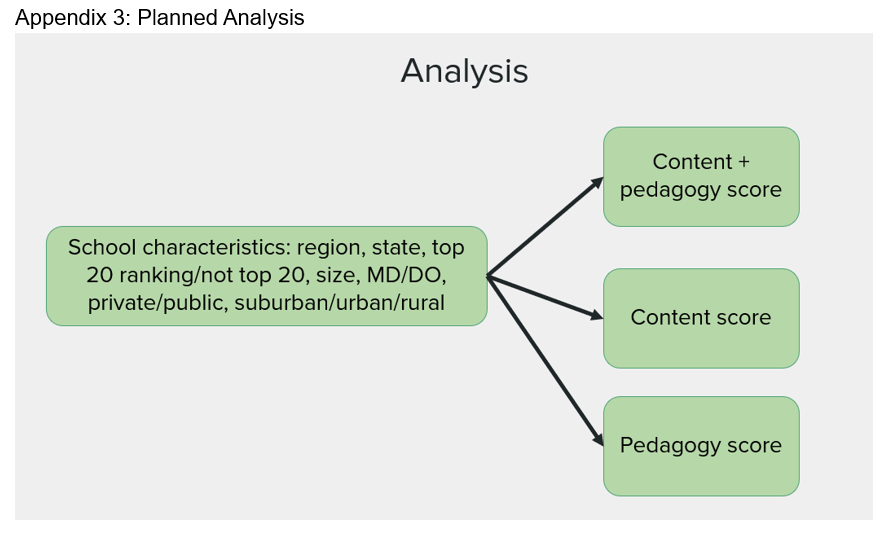

Analysis

Descriptive statistics will be conducted to calculate the average total, content, and pedagogy scores for the following school characteristics: US region, state, suburban/urban/rural, top 20 vs not top 20 ranking, school size, MD vs DO, and private vs public. Statistical analysis will be performed in SPSS using t-tests and ANOVA to determine if any of the school characteristics are associated with a curriculum comprehensiveness (higher content score), curriculum method effectiveness (pedagogy score), and overall curriculum quality (total content plus pedagogy score).

Implications

By characterizing the state of climate change curricula across US medical schools, this analysis will serve as a foundation for improving our future healthcare leadership’s preparedness to address what is perhaps the greatest threat to global health. In order to know how to improve the quality of the climate change instruction that medical students receive, the baseline must first be characterized. This study would be the first to comprehensively evaluate these curricula nationwide based on their content and use of effective climate change pedagogy.

The novel aim of this investigation means that the potential results will have widespread implications. This study could reveal gaps in the US medical education system that future interventions can aim to remedy. Therefore, these results could provide insight into designing future curricula that empower emerging physicians with the education they need to address the health consequences of climate change and advocate for solutions. The relationships between the content and pedagogy scores and characteristics of medical schools could signal to schools that they need to reform their climate change and health instruction. For instance, if the top 20 schools have higher quality scores compared to schools not ranked in the top 20, those schools not ranked highly would know they need to re-evaluate how they incorporate climate change into medical education. Or perhaps schools in the northeast score better than schools in the southern and western regions of the country. This would allow curriculum developers to focus on the climate change curricula of the medical schools outside the northeast, using the northeast school curricula as a model.

Future research should assess whether the high-quality climate change and health curricula are effective in preparing students for the challenges they will face in their future careers. A study could determine if medical schools with climate change curricula that score higher on the measures of content and pedagogy in this study are more successful in impacting students. Such an investigation could measure whether student knowledge, perceived preparedness to address the health complications of climate change, perceived preparedness to advocate for climate change solutions, and motivation to engage in climate advocacy are associated with the quality of their school’s curriculum as measured by the content and pedagogy scores. This would provide insight as to whether these scores accurately measure of how effective a curriculum is in imparting knowledge onto students, cultivating a sense of preparedness, and inspiring and motivating students to address the health consequences of climate change in their future practice.

Conclusion

Climate change is an increasingly important determinant of health, with many professional organizations calling it the “greatest threat to global health in the twenty-first century” (WHO, 2015). Physicians are an important stakeholder in this issue, and they are increasingly being called upon to play a role in climate change advocacy (Bugaj et al., 2020; Kreslake et al., 2018; Jameton, 2017; Spiby et al., 2008; Wellbery et al., 2018). Doctors treat the increasing number of patients affected by the health consequences of climate change and are influential figures with power in their communities, which places them in a unique position to advocate for climate change solutions to preserve health. Environmental health is not a standard part of the medical school curriculum, and instruction on climate change in this setting is notably understudied, but it is evident that few schools include climate change and health in their curricula (Hampshire et al., 2021; Omrani et al., 2020). Unfortunately, literature on the content and quality of medical school climate change and health curricula is sparse.

To address the lack of description of the quality of US medical schools’ climate change instruction based on the known effective methods of climate change pedagogy, this proposed study will attempt to fill this gap. This analysis will provide insight into designing future curricula that empower emerging physicians with the education they need to address the health consequences of climate change and advocate for solutions. The results of this study may serve as a foundation for a more standardized way of evaluating medical school climate change curricula that will set the country on a path to better prepare its future physician leaders to grapple with what some consider the leading health challenge they will face in their careers.

References

Bugaj, T. J., Heilborn, M., Terhoeven, V., Kaisinger, S., Nagy, E., Friederich, H.-C., & Nikendei, C. (2021). What do Final Year Medical Students in Germany know and think about Climate Change? - The ClimAttitude Study. Medical Education Online, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2021.1917037

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 22). Effects of climate change on health. Climate and Health. https://www.cdc.gov/climate-health/php/effects/index.html

Hampshire, K., Ndovu, A., Bhambhvani, H., & Iverson, N. (2021). Perspectives on climate change in medical school curricula—A survey of U.S. medical students. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 4(100033). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100033

Heydari, A., Partovi, P., Zarezadeh, Y. et al. (2023). Exploring medical students’ perceptions and understanding of the health impacts of climate change: a qualitative content analysis. BMC Med Educ 23, 774. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04769-1

Hu, S. R. & Yang, J.Q. (2023). Harvard Medical School Will Integrate Climate Change Into M.D. Curriculum. The Crimson. Retrieved May 8, 2025, from https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2023/2/3/hms-climate-curriculum/

Hughes, T. (2024). The physician's role in mitigating the climate crisis. Future Healthcare Journal, 11(4), 100173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fhj.2024.100173

Jameton, A. (2017, December 1). The Importance of Physician Climate Advocacy in the Face of Political Denial. AMA Journal of Ethics. Retrieved May 8, 2025, from https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/importance-physician-climate-advocacy-face-political-denial/2017-12

Kligler, B., Pinto Zipp, G., Rocchetti, C., Secic, M., & Ihde, E. S. (2021). The impact of integrating environmental health into medical school curricula: a survey-based study. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02458-x

Kreslake, J. M., Sarfaty, M., Roser-Renouf, C., Leiserowitz, A. A., & Maibach, E. W. (2018). The Critical Roles of Health Professionals in Climate Change Prevention and Preparedness. American Journal of Public Health, 108(2), S68. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304044

Marill, M. C. (2020). Pressured by students, medical schools grapple with climate change. Health Affairs, 39(12), 2050–2055. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaf...

Planetary Health Report Card Initiative. (2022, March 23). Metrics. Planetary Health Report Card. https://phreportcard.org/metrics/

Monroe, M. C., Plate, R. R., Oxarart, A., Bowers, A., & Chaves, W. A. (2019). Identifying effective climate change education strategies: a systematic review of the research. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 791–812. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842

Omrani, O. E., Dafallah, A., Paniello Castillo, B., Amaro, B. Q. R. C., Taneja, S., Amzil, M., Sajib, M. R. U., & Ezzine, T. (2020). Envisioning planetary health in every medical curriculum: An international medical student organization's perspective. Medical Teacher, 42(10), 1107–1111. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1796949

Pandve, H. T., & Raut, A. (2011). Assessment of awareness regarding climate change and its health hazards among the medical students. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 15(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5278.82999

Prüss-Ustün, A., Wolf, J., Corvalán, C., Bos, R., & Neira, M. (2016). Preventing Disease Through Healthy Environments: A Global Assessment of the Burden of Disease from Environmental Risks. Retrieved from https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/204585

Shariff, Y., Mushtaq, M., Shah, S. M. A., Malik, H., Abdullah, M., Jamil, M. U., Rehman, A., Hudaib, M., Manahil, Ahad, A. U., Mughal, S., & Eljack, M. M. F. (2024). Insight into medical students' environmental health consciousness regarding climate change's perceived impacts on human health. Environmental Health Insights, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/11786302241310031

Spiby, J., Griffiths, J., Hill, A., & Stott, R. (2008). Ten practical actions for doctors to combat climate change. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 336(7659), 1507. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39617.642720.59

Wellbery, C., Sheffield, P., Timmireddy, K., Sarfaty, M., Teherani, A., & Fallar, R. (2018). It’s time for medical schools to introduce climate change into their curricula. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 93(12), 1774–1777. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002368

World Health Organization. (2015). WHO calls for urgent action to protect health from climate change – Sign the call. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 11, 2025, from https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2015-who-calls-for-urgent-action-to-protect-health-from-climate-change-sign-the-call

Post a comment