Theory Integration Assignment: The Prenatal IPV Screening Framework

The United States has the highest maternal mortality of all high-income countries (Gunja et al., 2024). Yet, even most OBGYN physicians are surprised to learn that homicide is the number one cause of maternal death (M. E. Wallace, 2022). 80% of perinatal homicides are at the hands of loved ones as the result of an escalation of intimate partner violence (IPV) (Keegan et al., 2024; Roush, 2023). Studies demonstrate that screening for IPV during pregnancy can help mitigate these homicides (M. E. Wallace, 2022). Though the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends IPV screening at prenatal visits, only an estimated 39% of patients are screened (M. E. Wallace, 2022; Keegan et al., 2024). There is a paucity of research that aims to understand the factors that make doctors more likely to screen their patients for IPV, and there is no theoretical basis for how best to communicate the need for IPV screening to prenatal providers. I will develop a theory for this dilemma by combining variables from the Health Belief Model and the Stages of Precaution Adoption Process Model and then justify the potential uses of this combined framework.

Health Belief Model

The Health Belief Model (HBM) was first developed in the 1950s to better understand why people were not utilizing disease prevention measures (Alyafei & Easton-Carr, 2024). This model attempts to explain how people perceive health threats and decide to act upon them (NCI, 2005). The HBM emphasizes the role of six variables: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits of acting, perceived barriers to acting, cues to action, and self-efficacy. Perceived susceptibility encompasses an individual’s beliefs about their chances of being affected by a health threat (Alyafei & Easton-Carr, 2024). This understanding varies from person to person and context to context and is not always concordant with the actual threat to the individual; people may perceive low susceptibility to a threat when, in reality, they are at high risk. Perceived susceptibility may be altered using communication intervention to help individuals develop a more accurate perception of the likelihood that a specific risk will impact them (NCI, 2005). Perceived severity is an individual’s beliefs about the seriousness of a condition and the consequences that may result if they fail to take action to prevent it (Alyafei & Easton-Carr, 2024). This can be increased by educating people on the implications of health risks (NCI, 2005). For a person to take a health threat seriously, they need to perceive that they are both susceptible to that threat and that the consequences are severe.

The next two variables in the HBM are the perceived benefits and perceived. An individual’s perception of the benefit of doing something to reduce a risk depends on how well they think that action may mitigate their risk (Alyafei & Easton-Carr, 2024). Thus, many health behavior change interventions highlight the specific benefits of reducing risk (NCI, 2005). Perceived barriers are the costs of performing a behavior and the obstacles that stand in someone’s way, whether physical or psychological (Alyafei & Easton-Carr, 2024). Strategies to decrease an individual’s perception of barriers include correcting misinformation and providing strategies to overcome the obstacles. Individuals are more likely to perform health-protective actions when they have a high perception of the benefits and a realistic perception of the barriers. The fifth HBM variable, self-efficacy, is defined as an individual’s confidence in their ability to act (NCI, 2005). Self-efficacy is critical because an individual is more likely to perform a behavior if they believe they are capable of doing it successfully (Alyafei & Easton-Carr, 2024). Interventions to increase self-efficacy include trainings to empower individuals with confidence to perform a task (National Cancer Institute, 2005). Finally, the cues to action are the sixth and final variable in the HBM. Cues influence an individual to take action and can originate from the external surroundings or be internal to the individual (Alyafei & Easton-Carr, 2024). Cues to action ready an individual to make a behavior change and may include guidance on how to perform an action and reminders to do so (NCI, 2005).

Precaution Adoption Process Model

The Precaution Adoption Process Model (PAPM) is a stages of change model describing how individuals progress from being unaware of a health risk to maintaining a behavior change. According to this model, individuals at different stages of behavior change face different barriers (NCI, 2005). Thus, various strategies are required to move from one stage to the next. Individuals start unaware of a health issue (Stage 1) and progress to the next stage when they learn about that risk (Weinstein et al., 2008). At this point, they are aware of the issue but are unengaged by it (Stage 2). Once they become engaged, they move onto the process of deciding to act (Stage 3) (Weinstein et al., 2008). From this point, they will make a decision either to act (Stage 5), or not to act (Stage 4) (Weinstein et al., 2008). Those who choose to act may move to initiate that behavior in the action stage (Stage 6) (Weinstein et al., 2008). The model also recognizes that a single instance of behavior change is often insufficient; instead, a pattern of behavior change is frequently necessary to reduce a health risk. Thus, the final stage is maintaining the behavior change over time (Stage 7) (Weinstein et al., 2008). The PAPM also recognizes that though individuals progress through these stages in sequence, they may move forward and backward from the deciding stage to the maintenance stage.

Gaps

Neither the HBM nor the PAPM have been applied to the behavior of doctors screening pregnant patients for IPV to mitigate homicide risk. The HBM has been successfully applied to help women experiencing IPV, but not in the context of pregnancy. For instance, one study found that an intervention addressing self-efficacy, perceived barriers, and perceived benefits helped women who were not pregnant cope with IPV (Rakhshani et al., 2024). The HBM alone is insufficient for understanding how doctors decide whether to screen their prenatal patients for IPV because the model does not account for the fact that the susceptibility, severity, and benefits of this behavior are perceived by doctors not for themselves but for their patients. Additionally, the HBM fails to specify when each variable acts during the behavior change process. On the other hand, the PAPM may provide a framework for the sequence of changes in the process of deciding to screen a patient for IPV. The PAPM has not been applied to any health behavior change in the context of IPV, and the only violent context it has been studied in is cyberbullying in adolescents (J. Chapin, 2016). Furthermore, the PAPM does not account for the variables influencing each step in the behavior change process. Thus, I will fill this gap by developing a comprehensive theory combining elements of the HBM and the PAPM to explain doctors’ decisions to screen patients for IPV. I will include the timing of each variable that influences this behavior. This model is called the Prenatal IPV Screening Framework.

Prenatal IPV Screening Framework

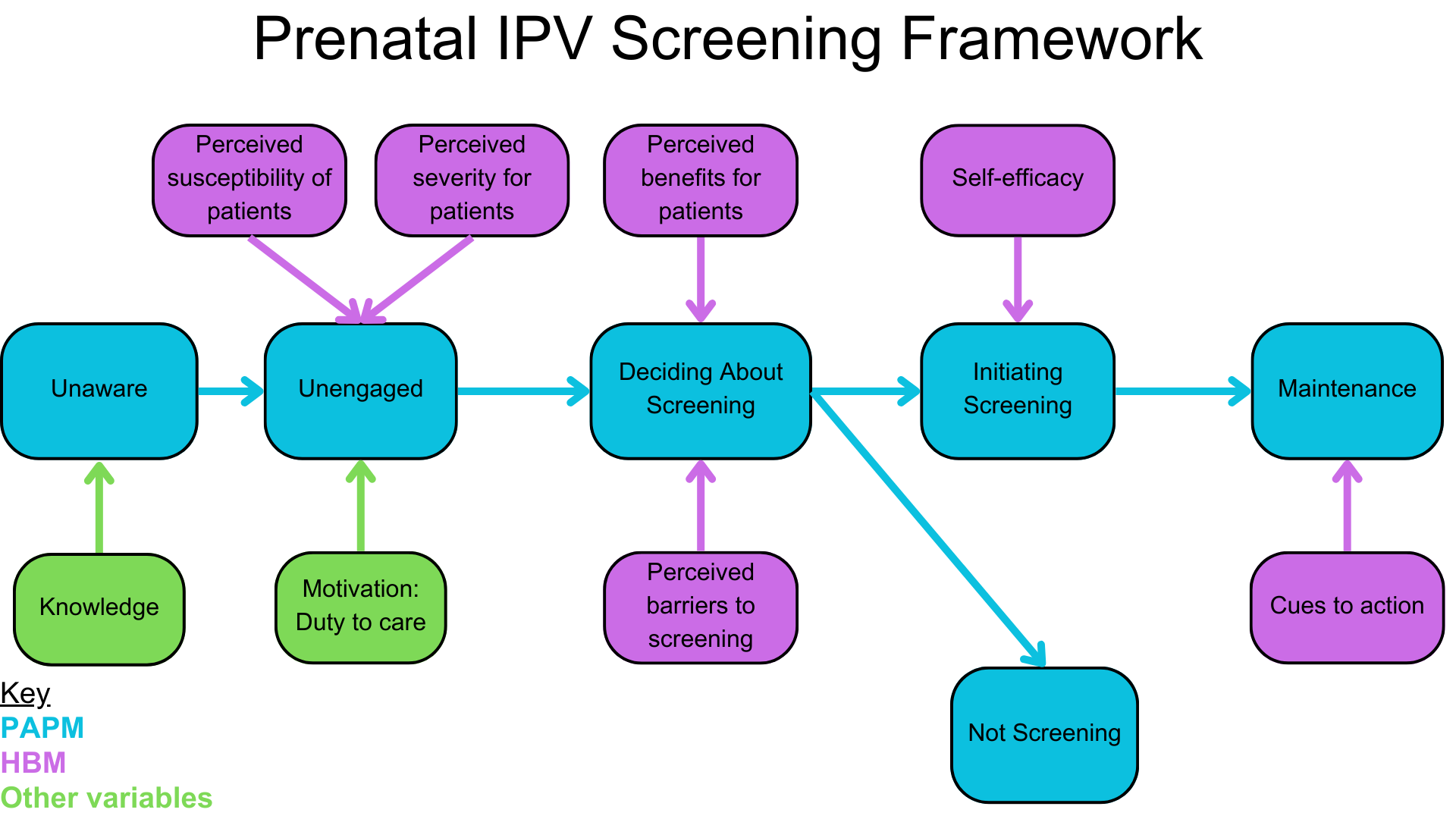

In the above framework, the HBM variables are purple, the PAPM stages are blue, and the additional variables are green. The blue arrows indicate the linear progression through time as a doctor learns about IPV in pregnancy, considers screening, acts, and then maintains their screening practices. The purple and green arrows are the variables that influence each step of this process. Ideally, doctors would progress through these stages linearly without backward regression, but this model also considers this possibility.

The model starts with doctors being unaware of the issue of perinatal homicide and its association with IPV. This is essential because most OBGYNs fall into this category, as studies show that healthcare providers underestimate the risk of peripartum IPV and homicide (Lee et al., 2019). Doctors can advance from this stage when they acquire knowledge about the scope of IPV and homicide in pregnancy. From there, they move onto a brief stage of being unengaged. Doctors’ recognition of the perceived severity of IPV during pregnancy and the perceived susceptibility of pregnant patients to homicide engages them because they see this issue as relevant to their clinical practice. This is a key difference from the variables in the HBM because this new model recognizes that it is the perception of one individual (doctor) on how a health risk affects another individual (pregnant patients) that is relevant. Information that may influence perceived susceptibility and perceived severity includes that up to 28% of expectant mothers experience physical violence and that women who experience IPV while pregnant are twice as likely to be killed as victims of IPV who are not pregnant (Bailey, 2010; Modest et al., 2022). Another important factor considered here, but not included in the HBM, is the motivation of physicians to provide high-quality, evidence-based care for their patients. Much work demonstrates that motivation is a mediating variable between physician learning and practice change (Williams et al., 2014). A systematic review found that physicians’ intrinsic motivation was associated with higher-quality patient care (Veenstra et al., 2022). Another study revealed that a clinician’s commitment to screening is the strongest predictor of women being screened for IPV and referred for support services (J. R. Chapin et al., 2011). Thus, an understanding of the relevance of IPV and homicide to their patients is likely to trigger physician’s motivation to help patients and engage them on the issue.

After becoming engaged by the importance of IPV screening to prevent perinatal homicide, physicians will enter a stage of deciding if they will act upon this threat by screening their patients for IPV. The variables relevant to this stage of the model include physicians’ perception of the benefits of screening for IPV at prenatal visits and the perceived barriers. For instance, there are clear benefits to screening for IPV in pregnancy, as this population is particularly vulnerable to homicide. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening for IPV at prenatal visits based on the results of numerous studies (Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, 2012). The fact that IPV screening is evidence-based and lifesaving during pregnancy will demonstrate to physicians the benefits of adopting screening into their practices (Miller et al., 2021). Physicians report several barriers to IPV screening, including their limited knowledge about IPV in pregnancy, their heavy workload, appointment time constraints, and feeling ill-equipped to help patients when they screen positive (Clements et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2024). These are valid concerns as IPV screening may be another task physicians’ busy schedules and one they do not know how to address. In order for physicians to weigh the benefits of screening for IPV higher than the potential costs of doing so, these barriers must be addressed. For instance, a program that increases physicians’ knowledge of IPV screening and covers strategies they can use to implement screening into their prenatal practices will help diminish their perceptions of these barriers.

At this point in their progression through this model, physicians may decide to initiate screening if the perceived benefits for patients outweigh the costs of implementing a screening program for themselves. On the other hand, they may choose not to if the barriers to screening patients outweigh their perception of the benefits. For those who decide that screening is worth pursuing, the final variable mediating their likelihood of screening is their self-efficacy in performing screening and helping those who screen positive. Providers get limited education on IPV screening specific to pregnancy, and they commonly cite a lack of confidence in their abilities to help patients as a significant factor preventing them from screening pregnant patients for IPV (Ibrahim et al., 2021). Studies show that self-efficacy mediates the relationship between motivation and practice change and that healthcare providers range in their self-efficacy regarding their ability to screen for IPV (Williams et al., 2014; J. R. Chapin et al., 2011). However, self-efficacy is modifiable, so if physicians are armed with greater self-efficacy in this context, they will be more likely to initiate IPV screening into their practice. A study of one intervention involving an IPV screening training for physicians found that it led to greater reported self-efficacy (J. R. Chapin et al., 2011). Finally, physicians should also progress to the last stage, which is the maintenance of their IPV screening practices. An important variable affecting their likelihood of successful maintenance is the presence of cues to action. Adding stimuli that remind them to initiate the new IPV screening behavior in its appropriate context can help create a lasting habit (NCI, 2005). An example of a cue would be an EMR alert reminder. One randomized clinical trial found that an EMR alert increased the screening rate for IPV from 45 to 65% (Lenert et al., 2024).

Implications

The Prenatal IPV Screening Framework may be considered when developing programs to increase doctors' likelihood of screening for IPV during pregnancy. By considering how physicians move through this model and which variables act at specific points in the process, we can develop better communication interventions to encourage more IPV screening. For instance, a lecture and training on prenatal IPV screening could help doctors progress through most phases of this framework. The lecture can first make physicians aware of the problems of IPV and homicide during pregnancy. They will become engaged when they accurately perceive their patients' susceptibility and severity of IPV. Physicians’ intrinsic motivation to help their patients will solidify their engagement. They can decide whether to screen screening as they learn how an IPV screening program will benefit their patients and are taught how to address barriers to implementing IPV screening into their busy practices. To get physicians to take action, self-efficacy training could empower them with the confidence to screen patients and assist those who report IPV successfully. They could maintain their IPV screening program by integrating it into their daily practice using an EMR reminder at the first prenatal visit in each trimester.

The successful implementation of this Prenatal IPV Screening model would lead to more fruitful prenatal IPV screening programs that identify more pregnant victims. Identification of victims is essential to mitigate their risk of homicide and decrease the burden of violence on pregnant women. As IPV is so closely entwined with peripartum homicide, this framework has the potential to help ameliorate the crisis of homicide as the number one cause of maternal mortality in the US. Additionally, because the burden of maternal homicide falls most heavily on people of color, younger women, women in states with inadequate prenatal care, and those with lower socioeconomic status, this framework could help address disparities in maternal mortality (Wallace, 2022).

References

Alyafei, A., & Easton-Carr, R. (2024). The health belief model of behavior change. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606120/

Bailey, B. A. (2010). Partner violence during pregnancy: prevalence, effects, screening, and management. International Journal of Women’s Health, 2, 183–197. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijwh.s8632

Chapin, J. (2016). Adolescents and cyber bullying: The precaution adoption process model. Education and Information Technologies, 21(4), 719–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-014-9349-1

Chapin, J. R., Coleman, G., & Varner, E. (2011). Yes we can! Improving medical screening for intimate partner violence through self-efficacy. Journal of Injury & Violence Research, 3(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v3i1.62

Clements, P. T., Holt, K. E., Hasson, C. M., & Fay-Hillier, T. (2011). Enhancing assessment of interpersonal violence (IPV) pregnancy-related homicide risk within nursing curricula. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 7(4), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939... on Health Care for Underserved Women. (2012). Intimate Partner Violence. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2012/02/intimate-partner-violence#:~:text=Physicians%20should%20screen%20all%20women,available%20prevention%20and%20referral%20options.

Gunja, M. Z., Gumas, E. D., Masitha, R., & Zephyrin, L. C. (2024). Insights into the U.S. maternal mortality crisis: An international comparison. Commonwealth Fund. https://doi.org/10.26099/CTHN-ST75

Ibrahim, E., Hamed, N., & Ahmed, L. (2021). Views of primary health care providers of the challenges to screening for intimate partner violence, Egypt. La Revue de Sante de La Mediterranee Orientale [Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal], 27(3), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.20.125

Keegan, G., Hoofnagle, M., Chor, J., Hampton, D., Cone, J., Khan, A., Rowell, S., Plackett, T., Benjamin, A., Bhardwaj, N., Rogers, S. O., Zakrison, T. L., & Cirone, J. M. (2024). State-level analysis of intimate partner violence, abortion access, and peripartum homicide: Call for screening and violence interventions for pregnant patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 238(5), 880–888. https://doi.org/10.1097/XCS.0000000000001019

Lee, S., Holden, D., Webb, R., & Ayers, S. (2019). Pregnancy related risk perception in pregnant women, midwives & doctors: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2467-4

Lenert, L., Rheingold, A. A., Simpson, K. N., Scherbakov, D., Aiken, M., Hahn, C., McCauley, J. L., Ennis, N., & Diaz, V. A. (2024). Electronic health record-based screening for intimate partner violence: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 7(8), e2425070. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.25070

Miller, C. J., Adjognon, O. L., Brady, J. E., Dichter, M. E., & Iverson, K. M. (2021). Screening for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings: An implementation-oriented systematic review. Implementation Research and Practice, 2, 263348952110398. https://doi.org/10.1177/263348... Cancer Institute. (2005). Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/theory.pdf

Rakhshani, T., Poornavab, S., Kashfi, S. M., Kamyab, A., & Jeihooni, A. K. (2024). The effect of educational intervention based on the health belief model on the domestic violence coping skills in women referring to comprehensive rural health service centers. BMC Women’s Health, 24(1), 596. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03433-0

Roush, K. (2023). Mitigating homicide risk during pregnancy. The American Journal of Nursing, 123(5), 9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000933872.92011.1e

Veenstra, G. L., Dabekaussen, K. F. A. A., Molleman, E., Heineman, E., & Welker, G. A. (2022). Health care professionals’ motivation, their behaviors, and the quality of hospital care: A mixed-methods systematic review. Health Care Management Review, 47(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000284

Wallace, M. E. (2022). Trends in pregnancy-associated homicide, United States, 2020. American Journal of Public Health, 112(9), 1333–1336. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306937

Weinstein, N. D., Sandman, P. M., & Blalock, S. J. (2020). The precaution adoption process model. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology (pp. 495–506). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119057840.ch100

Williams, B. W., Kessler, H. A., & Williams, M. V. (2014). Relationship among practice change, motivation, and self-efficacy. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 34 Suppl 1(Supplement 1), S5-10. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21235

Wong, J. Y.-H., Zhu, S., Ma, H., Ip, P., Chan, K. L., & Leung, W. C. (2024). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: To screen or not to screen? Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 97(102541), 102541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2024.102541

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Post a comment