Endo Ed: Addressing the Crisis of Untreated Menstrual Pain and Endometriosis

Health Problem

Dysmenorrhea, also known as period pain, is the most common menstrual symptom and can occur in the presence or absence of pelvic pathology (Dysmenorrhea and Endometriosis in the Adolescent, n.d.). Menstrual pain can be debilitating, and it often affects menstruators’ ability to fully participate in daily tasks such as school, work, and social events. For instance, dysmenorrhea is the leading cause of short-term school absenteeism among female adolescents, and 12% of 14- to 20-year-old girls miss school or work each month due to their menstrual pain (Zannoni et al., 2014). Furthermore, one in four women report regularly taking medication for period pain without having seen a physician to identify the cause (Zannoni et al., 2014). Other research confirms that adolescents are especially vulnerable to delays in accessing menstrual pain treatment (Mann et al., 2013). Given the evidence that untreated dysmenorrhea prevents girls and women from fully living their lives, disorders of menstruation and their benign gynecological causes present a pressing public health concern that is largely neglected by the healthcare system.

Of all the benign gynecological conditions that cause menstrual pain, one stands out among the rest. Endometriosis is one of the most prevalent benign gynecological conditions, especially among young menstruators, and is particularly debilitating. Endometriosis is a disease characterized by a tissue similar to the uterine lining growing ectopically in the pelvis and other organs. This tissue is hormonally responsive, perpetuating cyclical inflammation and pain. It is estimated that 1 in 10 menstruating women are affected by endometriosis, but many go undiagnosed for years (NYS DOH, n.d.). Endometriosis is not only significantly prevalent, but it results in significant impairment, as measured by endometriosis causing the highest number of years lost to disability (YLDs) among all benign gynecological conditions (Wijeratne et al., 2024). Menstruators commonly struggle for years before they are diagnosed and appropriately treated for endometriosis. The average delay in diagnosis for endometriosis in the US varies in the literature, with some citing as low as 6.7 years from the onset of symptoms to more than 11 years (Fryer et al., 2024; Parasar et al., 2017). Not only does this delay lead to pain and suffering for hundreds of thousands of menstruators, but it is also potentially contributing to the overburdening of the healthcare system. Treating endometriosis after years of progression is more costly, and research demonstrates that the diagnostic delay of endometriosis leads to higher healthcare utilization (Surrey et al., 2020).

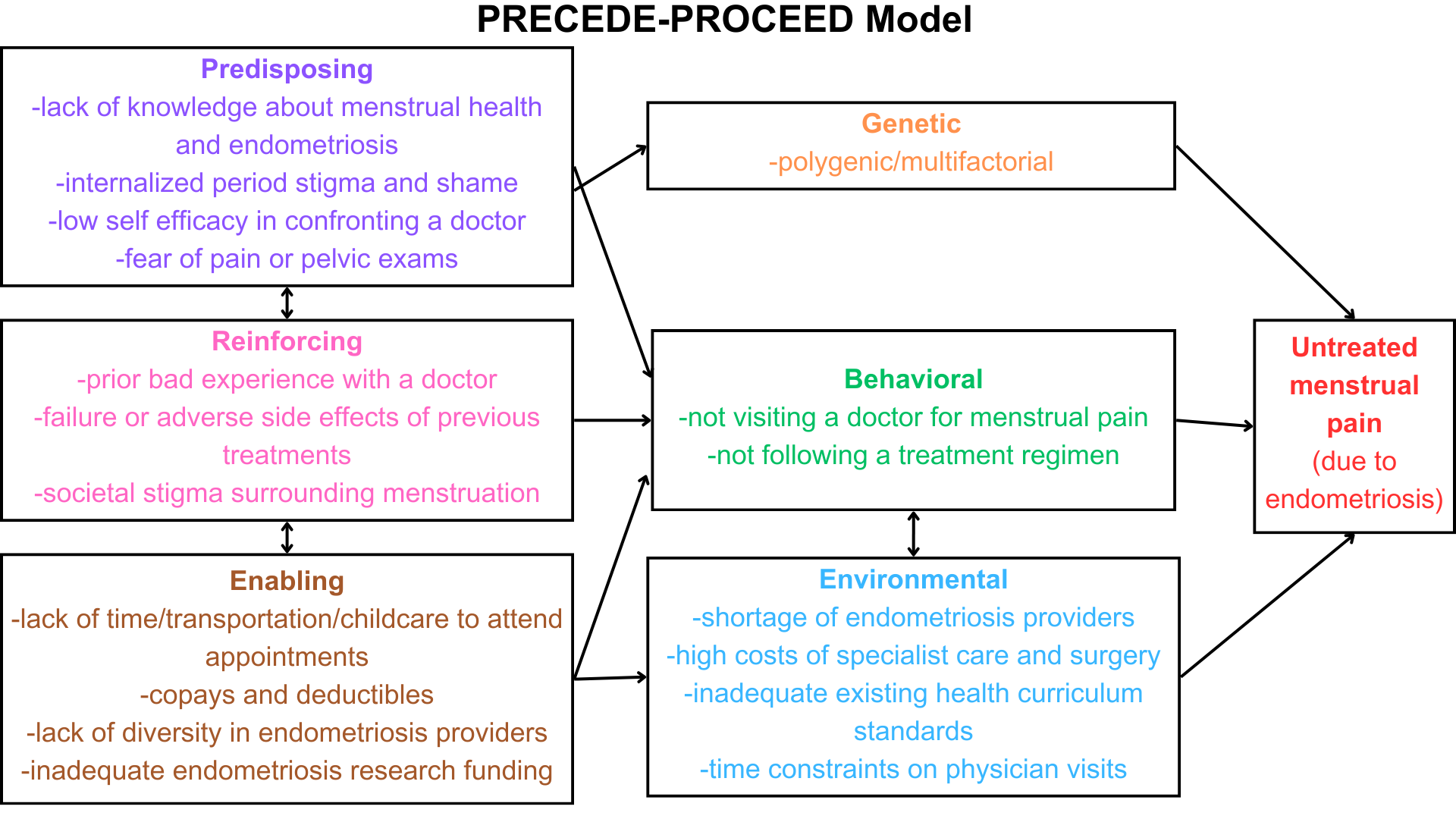

The PRECEDE-PROCEED Model emphasizes the importance of understanding the genetic, behavioral, and environmental factors and the predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling factors prior to designing an intervention to address a health problem (Green & Kreuter, 1991). This community health assessment and intervention employs this model to address the crisis of untreated endometriosis among young adults.

Genetic Factors

Research suggests that there is a polygenic and multifactorial genetic component to endometriosis (Hansen & Eyster, 2010). Unfortunately, this does not lend itself easily to community intervention. Therefore, this factor would not be an ideal target for intervention within a public health program and will not be addressed further here.

Behavioral and Corresponding Predisposing, Enabling, and Reinforcing Factors

Several behavioral factors contribute to the crisis of untreated endometriosis. The most salient ones are not visiting a doctor for treatment and not following a prescribed treatment regimen. There are many reasons why someone may not see a doctor to seek menstrual pain treatment, but evidence demonstrates that a lack of knowledge of menstrual health is an especially important predisposing factor (Regional Health-Americas, 2022). Studies have connected a lack of knowledge of menstrual abnormalities to the decade-long average delay in diagnosis of endometriosis, as menstruators who do not have a general understanding of menstrual health are less likely to report symptoms to their doctors (Fryer et al., 2024; Khan et al., 2022). It makes sense that if menstruators are unaware of what constitutes normal menstruation, they cannot determine if their own experiences warrant seeking care.

Other predisposing factors that contribute to the behavior of not seeing a doctor for menstrual pain include the internalized period stigma and the resulting shame of discussing menstruation. Menstrual stigma is defined as the “negative perception of menstruation and those who menstruate, characterizing the menstruating body as abnormal and abject” (Olson et al., 2022). Societal stigma powerfully perpetuates misogynistic stereotypes that women are “irrational,” “emotional,” and “hysterical.” This makes it a reinforcing factor. The shame that shrouds menstruation leads to the normalization of menstrual pain and prevents women from discussing menstruation, even with their healthcare providers (Olson et al., 2022).

Another predisposing factor leading to a decreased likelihood of menstruators seeing a doctor for menstrual pain is low self-efficacy regarding the ability to advocate for oneself in a medical setting. Perceived self-efficacy is defined as “a person’s ability to implement situation-specific behaviors in order to attain established goals, expectations, or designated types of outcomes” (Hoffman, 2013). Many menstruators do not feel comfortable advocating for themselves when a doctor fails to take their concerns seriously, which is an all too common occurrence with menstrual pain (Long et al., 2023). A final predisposing factor that can prevent many women from seeing a doctor for their menstrual issues is the fear and anxiety of seeing a gynecologist and the pelvic exam or invasive procedures that might be necessary (O’Laughlin et al., 2021).

Reinforcing factors occur after a behavior and make it more likely that this behavior will be repeated (Green & Kreuter, 1991). Reinforcing factors that contribute to the low likelihood that a woman experiencing menstrual pain will visit an endometriosis specialist first include the societal stigma about menstruation, as mentioned above. Another factor that reinforces avoidant behavior when it comes to the gynecologist is a previous negative experience with a doctor or hearing about the bad experiences of others. It is no secret that the healthcare system largely neglects the needs of menstruators. 29% of women report that a doctor has dismissed their concerns and another 15% report that a provider has questioned their truthfulness (Long et al., 2023). Additionally, 1 in 10 women report experiencing discrimination during a healthcare visit. Prior negative experiences with doctors who didn’t listen to their concerns and were judgmental make women less likely to seek care in the future (Long et al., 2023).

A second behavioral factor that may lead to unaddressed menstrual pain is failing to follow a prescribed treatment regimen. While poor adherence to treatment may be a plausible explanation for unaddressed menstrual pain, there is a paucity of research in this area. At the same time, it is reasonable to expect that some menstruators may not take endometriosis medications because of the intolerable side effects. For instance, hormonal therapies such as oral contraceptives containing progesterone and progesterone can lead to weight gain and acne and cause mood changes and changes in sex drive (Flickr, n.d.). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) treatments essentially induce a menopause-like state, leading to the chance of symptoms like hot flashes, nausea, difficulty sleeping, and mood changes (Flickr, n.d.). Patients are more likely to discontinue their prescribed endometriosis treatment if they experience unacceptable side effects (Nirgianakis et al., 2021). Furthermore, endometriosis surgery can be invasive and may affect one’s fertility, and these may be reinforcing factors for noncompliance with a treatment regimen (Flickr, n.d.).

Enabling factors are antecedents that make it more likely for a behavior to occur (Green & Kreuter, 1991). Several enabling factors prevent menstruators from seeking endometriosis care or following a treatment regimen. Some menstruators may not be able to get off from work or be able to find childcare for their visits, treatment, and recovery. A lack of transportation likewise enables the avoidance of seeing a doctor for menstrual pain. It is also vital to consider the high costs of medical care as an enabling factor contributing to the avoidance of gynecologists. Out-of-pocket costs for endometriosis treatment for the uninsured cost thousands of dollars, and copays, deductibles, and out-of-network costs are prohibitive for the insured (Fuldore et al., 2011).

Environmental Factors and Corresponding Enabling Factors

Environmental factors associated with untreated menstrual disorder pain include the shortage of healthcare providers competent in treating endometriosis, the high costs of specialist and surgical care, the inadequate existing sexual health curriculum standards, time constraints on physician visits, and a lack of adequate funding for endometriosis research. First, the shortage of healthcare providers competent in treating endometriosis is a significant factor preventing menstruators from being adequately treated for endometriosis. While all OBGYN residents are trained in diagnosing and treating benign gynecological conditions, not every OBGYN provider is trained in endometriosis management per the most up-to-date guidelines. According to the Endometriosis Foundation of America, out of over 40,000 OB/GYNs in the US, there are only around 100 who are skilled in the most up-to-date endometriosis treatment options (Endometriosis Foundation of America, 2010). Additionally, some providers do not take women’s pain seriously, preaching that menstrual pain is normal and not something that needs to be addressed (Wiggleton-Little, 2024).

The lack of competent endometriosis providers is in part due to the enabling factors of inadequate training for OBGYNs in endometriosis care and the lack of adequate funding for endometriosis research, leading to a knowledge gap (Ellis et al., 2022; Hudson, 2022). The limited diversity of endometriosis specialists is an enabling factor that exacerbates the provider shortage and significantly impacts menstruators’ ability to get their menstrual pain addressed. Some patients request care from a female OBGYN for religious or cultural reasons, concerns about privacy, or a history of sexual abuse (Shalowitz et al., 2022). Other patients may prefer providers with similar ethnic or cultural backgrounds, especially if they are not fluent in English. While research is mixed as to whether patient-physician gender or racial/ethnic concordance is beneficial to patient outcomes, patient satisfaction is usually higher with greater concordance (Takeshita et al., 2020). Data shows that the racial and ethnic diversity of OBGYNs lags behind the US demographic breakdown (López et al., 2021).

A second environmental factor contributing to untreated endometriosis is the high cost of healthcare. Many menstruators may be unable to afford visits to specialist physicians whether or not they have insurance. Specifically, the threat of copays and deductibles enables menstruators to put off seeing specialists for their menstrual pain. It is well understood that people who cannot afford healthcare are generally less likely to utilize it (Lopes et al., 2024). Additionally, some insurance plans require a referral from a primary provider, which only increases the cost of care. Like in many other areas of healthcare, cost is prohibitive for menstruators seeking treatment for their menstrual pain.

Another environmental factor that contributes to this endometriosis crisis is the inadequate health curriculum standards. The US education system does a poor job of teaching sexual health in general, and often, these programs focus solely on STI and pregnancy prevention. Only 39 states mandate any sex education in schools, and while there are also state-level regulations, most of the decisions are left up to the individual school districts (State of sex education in USA, n.d.). There is a paucity of data on how many of these programs include education about menstruation, but according to UNICEF, only 39% of schools worldwide provide menstrual health education (UNICEF, 2024). This creates a patchwork of inconsistent education on reproductive health that neglects menstrual health. While there is no study on the adequacy of these education programs, data indicates that these programs are inadequate in imparting menstrual knowledge to students. One large survey revealed that 40% of respondents had an incomplete understanding of the ovulatory cycle (Olowojesiku et al., 2021). Since menstruators are not being explicitly taught about menstrual health and endometriosis, there are gaps in their knowledge that may be filled with misinformation from less reliable sources. The time constraints on physician visits are another environmental factor that complicates this situation, as most doctors lack the appropriate time to counsel and educate patients in their 15-minute appointment slots. Many menstruators do not have access to information regarding what symptoms constitute a normal period, and there is no easily accessible guide that informs menstruators about what symptoms indicate the need for evaluation.

The most important behavioral factor I identified as leading to untreated endometriosis is the pattern of menstruators failing to seek care for their menstrual disorders. This is upheld by the predisposing factor of a lack of knowledge about menstrual health and endometriosis and a lack of self-efficacy in advocating in the medical setting. The most salient environmental factor is the shortage of endometriosis providers, which is enabled by the lack of diversity in the physician population and inadequate funding for endometriosis research. These will serve as the basis of the following intervention program.

Overview of the Community

The community most impacted by untreated endometriosis is young adults who menstruate. Specifically, I will narrow my focus to undergraduates at Stony Brook University. I chose this community first because menstrual disorders commonly manifest during young adulthood, and most university undergraduates fall into this category as they are typically aged 18-22. Younger menstruators may also be more likely to be dismissed by a doctor when they bring up menstrual concerns compared to menstruators in their thirties. Undergraduates also have the independence to seek treatment for their menstrual disorders, which makes them an ideal target for an intervention that aims to increase the likelihood that they will seek out treatment. I chose Stony Brook Undergraduate menstruators specifically because I have easy access to this population, and it was feasible to conduct a community assessment and intervention. I decided not to include graduate students in my priority population because many are in the health science fields and likely have more knowledge of menstruation and endometriosis.

Community Needs

I further characterized my priority population using information available from the school. Stony Brook University is a State University of New York (SUNY) and is ranked the #1 public university in the state (US News, 2024). There were over 18 thousand undergraduate students for the fall 2024 semester, and 51% identified as female (Stony Brook Office of Communications, n.d.). This means that it is reasonable to conclude that there are over nine thousand undergraduate menstruators here. The demographic breakdown of this population is as follows: 1.2% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 47.3% Asian, 10.0% African American or Black, 16.0% Hispanic or Latino, 0.3% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Island, and 39.9% White (Stony Brook Office of Communications, n.d.). As of 2022, 80.7% of Stony Brook undergraduates are US citizens, and 27.4% are foreign-born. This demonstrates that although all members share the identity of being undergraduates at the same university, they are not a homogenous group and are instead composed of an array of diverse individuals.

To assess my population’s needs, I chose a questionnaire as a primary data collection method because it was an efficient and low-cost way to collect quantitative data (Green et al., 2022). A questionnaire was also beneficial because it allowed me to reach a more significant portion of the priority population than other assessment measures (Green et al., 2022). Additionally, some menstruators might feel more comfortable filling out an anonymous survey than participating in an interview or focus group (Green et al., 2022).

I developed a unique survey, combining elements from the Menstrual Distress Questionnaire (MEDI-Q), the Endometriosis Health Profile-30 (EHP-30), and the Endometriosis Impact Questionnaire (EIQ) (Moradi et al., 2019; Pontoppidan et al., 2023; Vannuccini et al., 2021). The survey consisted of 20 anonymous multiple-choice, short-answer, and Likert scale questions asking how menstruation affects menstruators’ daily functioning and how they cope with these issues. The questions also asked about respondents' knowledge of menstruation, menstrual history, and experiences navigating the healthcare system. I created the survey using Qualtrics (see Appendix 2) and contacted campus organizations. The Women in Healthcare undergraduate organization distributed the survey link to their members in their weekly email. I received seven responses to my survey, so it is essential to recognize that this small sample size may not be representative of my entire target community. If time permitted, I would have tried to reach more participants through other means of communication and perhaps offered an incentive to get more to participate. Nonetheless, my survey provided valuable insight into the needs of my priority population.

I identified my population’s knowledge gaps about menstrual health. It is important to note that I asked participants about their perceptions of their knowledge rather than assessing their actual knowledge, and there may be a discrepancy between the two. Most participants responded that they “maybe” knew how much bleeding in one day is considered normal. Responses regarding their knowledge of the normal pain level during menstruation were mixed. The participants were split between “no” and “maybe” on whether it is normal for a person to miss a day of school or work each month due to their period. Participants were unsure whether they knew the signs indicating if someone should seek care from a doctor regarding their menstrual health. One patient agreed that they knew how to recognize the signs of endometriosis, three said they had heard of the disorder but didn’t know the symptoms, and two had never heard of it. These results indicate knowledge gaps in this population’s understanding of endometriosis.

In response to questions about their own experiences with menstruation, several survey participants reported worrisome symptoms and interference with daily functioning. For instance, two participants indicated they had flow for more than seven days and one said they use more than six period products on their heaviest day. Most patients indicated that the worst pain they experience during menstruation is between a 5-7 on a ten-point scale, however, one patient reported that her menstrual pain is 10/10 in severity. Half of the patients indicated that they occasionally leak blood onto their clothes or bedsheets, a sign of abnormally heavy flow. All participants indicated that they experienced some level of worry about this leakage, with one saying they always are concerned. Half of the patients reported worrying about their menstrual symptoms worsening. Three indicated that their period symptoms cause them anxiety and feelings of embarrassment, which may indicate internalized stigma surrounding menstruation. One participant indicated that they often miss school or work due to their period. Two participants reported occasionally missing social events due to their period, and one reported frequently. Four participants reported often missing school, work, or social events due to their periods, and two said that their periods occasionally cause problems with their relationships. Taken together, these results indicate that members of this population experience worrisome menstrual symptoms.

Half of the participants reported previously seeing a doctor about their menstrual concerns, and all who saw a physician noted that they were not given a diagnosis. Two felt their doctor took their complaints seriously, one wasn’t sure, and one reported that they weren’t taken seriously. Three of these patients reported that they were not satisfied or unsure if they were satisfied with their treatment. Three patients were prescribed birth control pills, and one stated that their physician didn’t offer them any treatment. These results indicate that despite seeking medical care, some menstruators’ menstrual pain was still not adequately treated.

Another way to assess the needs of this community would be to conduct other forms of primary data collection, such as interviews and focus groups. First, I would ideally hold at least four focus groups, each consisting of 8-12 individuals (Leung & Savithiri, 2009). Focus groups allow participants to hear the experiences of others, which may make them more open to sharing their own feelings through “piggybacking” (Leung & Savitri, 2009). I would gather participants by using posters or emails to recruit individuals for interviews who report that they experience high menstrual pain. I chose this method of purposive and convenience sampling because I am most concerned with learning about those who experience impairing menstrual pain (Palinkas et al., 2015). Focus group discussions with menstruators would provide an abundance of qualitative data about their experiences of menstruation, including the amount of distress that their symptoms cause and how their period affects their ability to study, work, or socialize. I could also discover how they deal with their menstrual concerns, like whether they see a physician, take over-the-counter medications, or stay home on the worst days of their cycle. I would generate a list of guiding questions for the leader, but the conversation would be centered around the needs of the participants in the group. This approach provides subjective data about menstruators' needs and their quality-of-life concerns.

I would also assess the needs of my community by talking to key stakeholders, such as gynecologists, including specialists in endometriosis. Local gynecologists treat menstruators on campus with menstrual disorders, so it would be essential to get their perspective. Gynecologists would provide insight into the most common symptoms, quality of life concerns, and how menstruators are treated. These interviews would be a feasible option because I have contacts in the OBGYN department at Stony Brook Hospital. The perspective of gynecologists would be insufficient on its own but would be a great supplement to information gathered directly from the priority population.

Finally, I could verify the need in my community using secondary data. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of data on benign gynecological health; most county, state, and national data on women’s health has to do with pregnancy, oncology, and sexually transmitted infections. For instance, no data set from the CDC or NYS identifies the number of menstruators in an area or the prevalence of disorders of menstruation. This is no surprise because menstrual pain is not taken seriously by our culture, and the burden of menstruation is a largely unrecognized and unaddressed issue. If such data sets did exist, it would provide important objective information, such as the prevalence of endometriosis and the percentage of people who are being treated for menstrual pain. Secondary data I did have access to was previous studies of menstrual pain in select populations, which I discussed above in the literature review. While I would not find any data on my exact population because it is so specific, I found data on college-aged menstruators.

Community Assets

One asset of this community is their status as students enrolled in higher education. By their nature of being college students, this group is knowledgeable and motivated to learn. This may be essential for any educational intervention that aims to arm them with knowledge of endometriosis symptoms. Another asset present in this community is that almost all Stony Brook Undergraduates have health insurance as it is typically required for enrollment: 46.6% are on employee plans, 16.5% on Medicaid, none are on Medicare, 35.1% on non-group plans, and 0.189% are covered as active military or veterans (Stony Brook University, NY, n.d.). Access to health insurance is an important asset because insurance decreases the cost barrier to obtaining healthcare, which will make it more likely that students will be able to see a gynecologist for their menstrual disorders. The final asset of this community is that it is located in close proximity to Stony Brook Hospital and its affiliates, meaning that there are a large number of gynecologists in the area. The availability of these resources will be valuable in an intervention aiming to decrease pain and suffering due to untreated endometriosis.

Intervention Overview

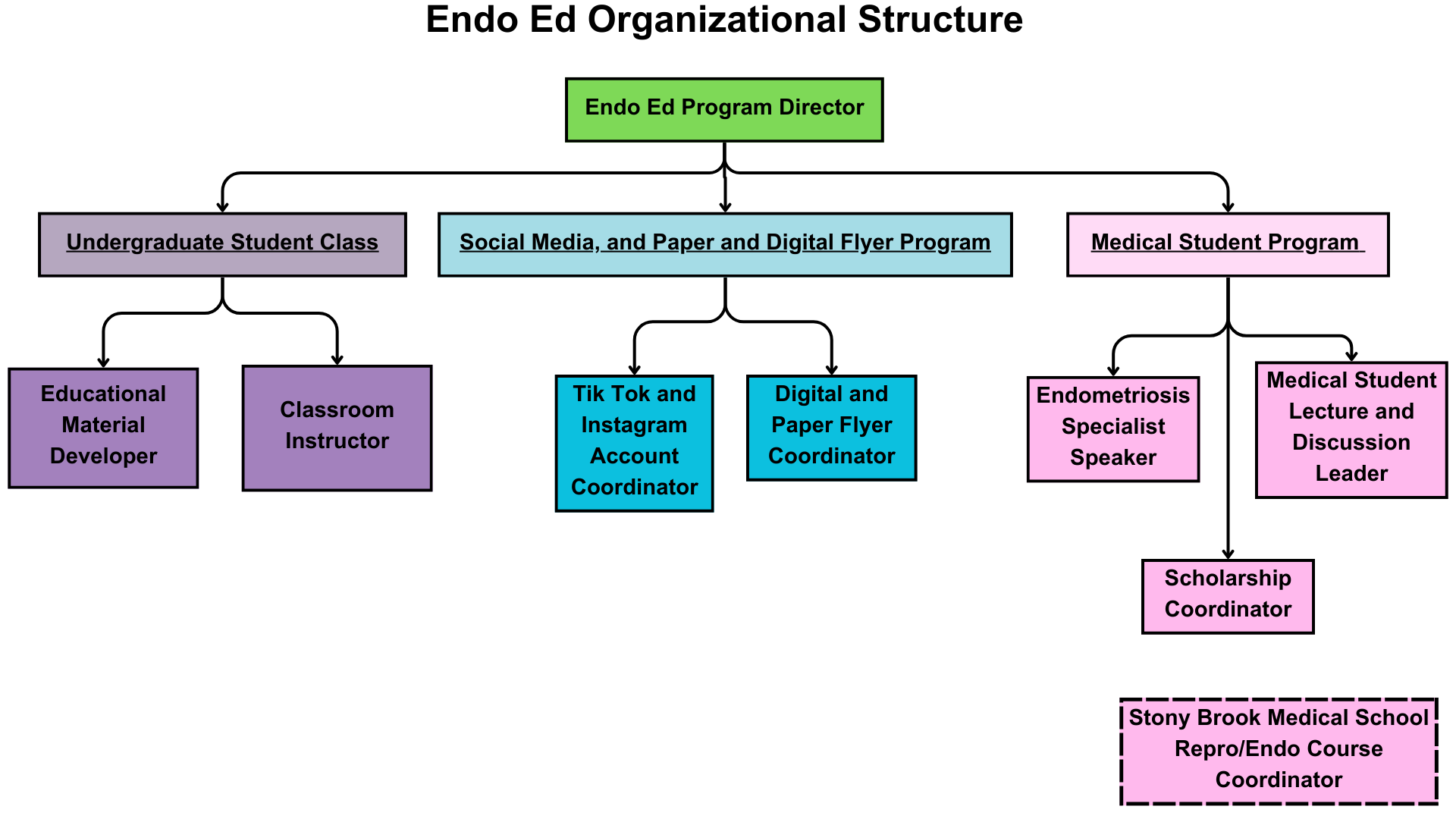

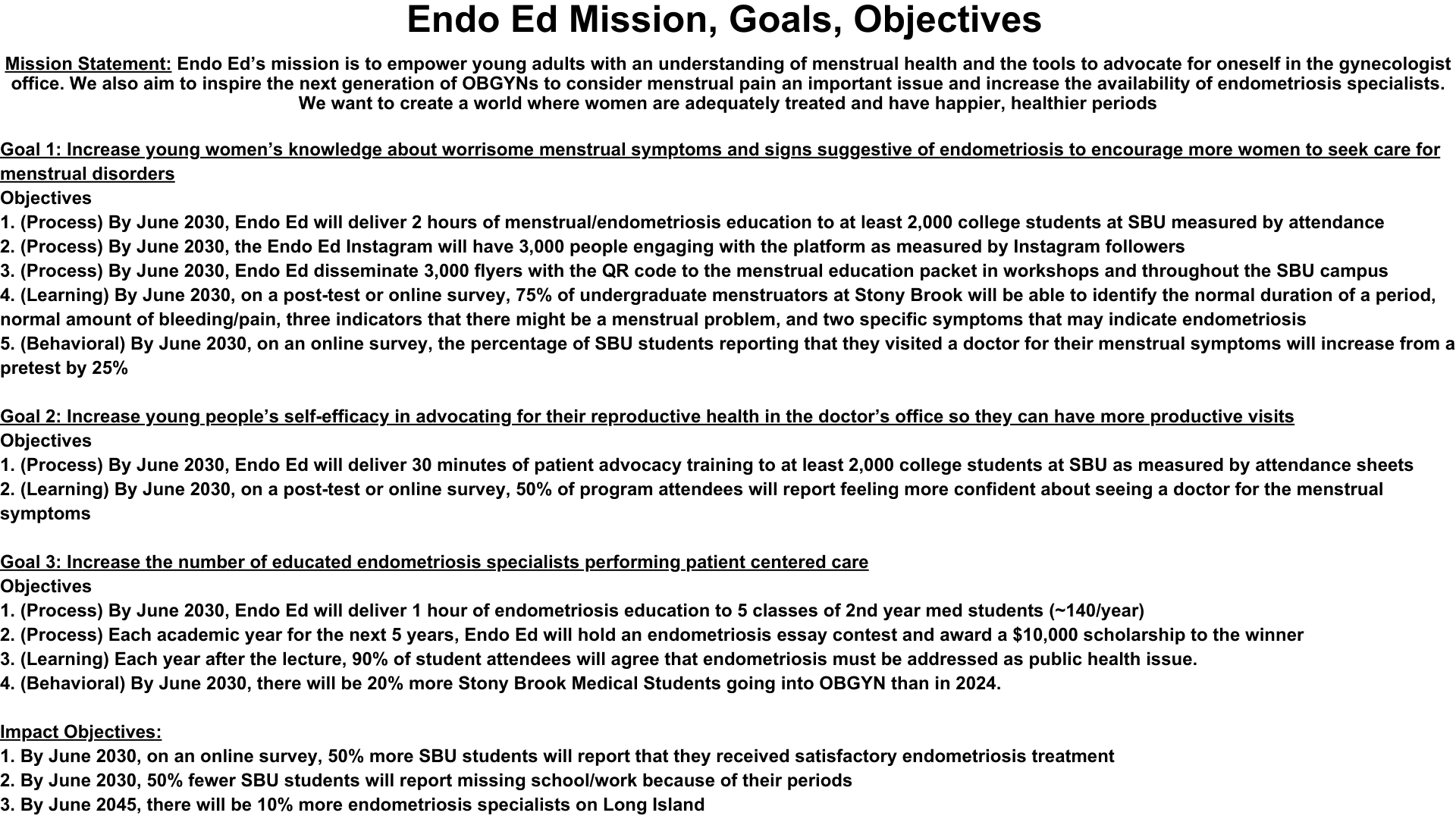

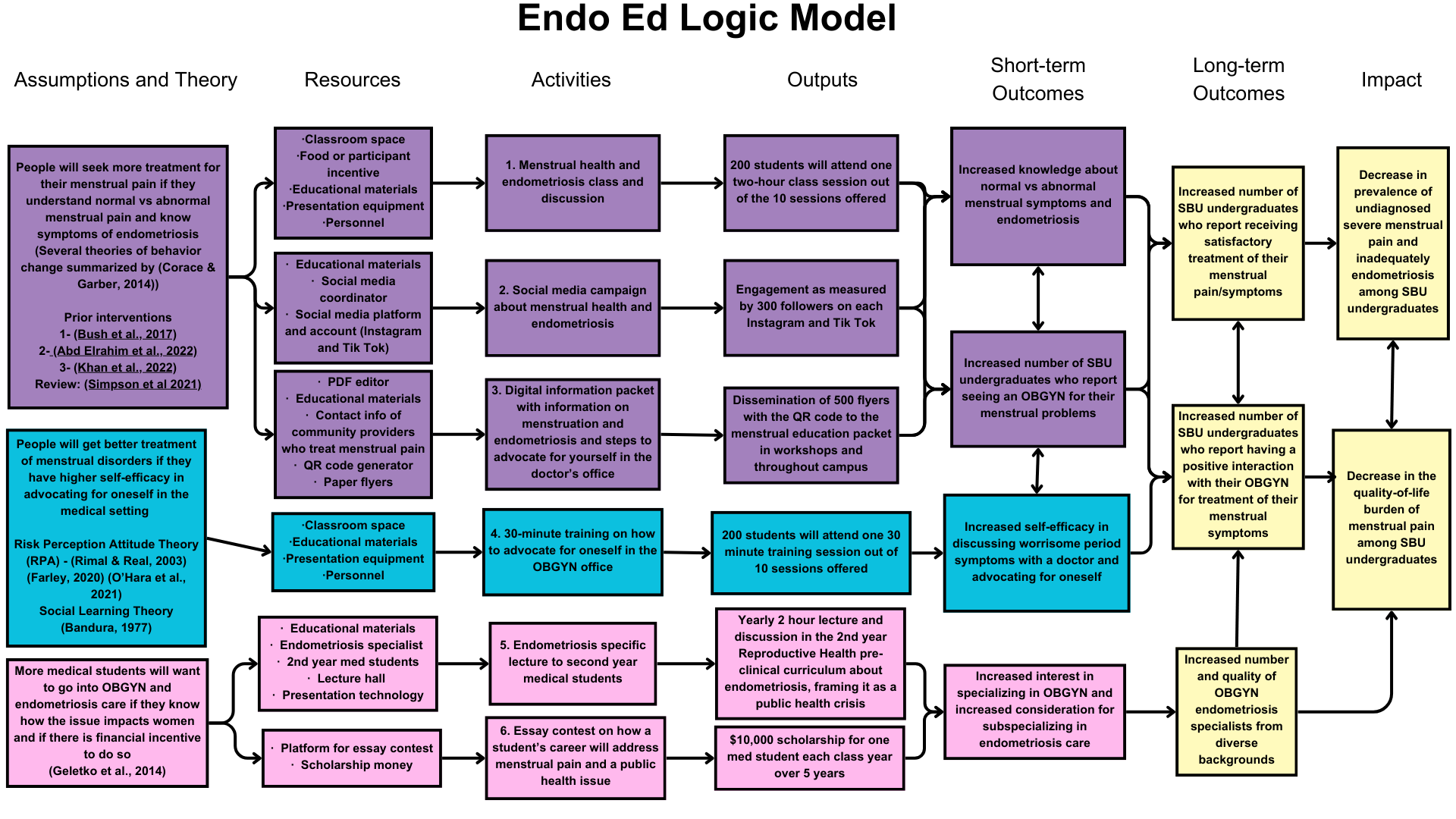

The most salient factors identified in this community health assessment, which will serve as the basis for our program, include not visiting a doctor to address menstrual pain (behavioral), and the shortage of endometriosis providers (environmental). There will be three arms to our program that address each of these issues and the predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling factors that lead to them. The program will be called “The Endometriosis Education Program,” or “Endo Ed” for short. The mission of Endo Ed is “to empower young adults with an understanding of their menstrual health and the tools to advocate for themselves in the gynecologist's office. We also aim to inspire the next generation of OBGYNs to recognize the importance of treating menstrual pain and increase the availability of endometriosis specialists. We want to create a world where menstruators are adequately treated to have happier, healthier periods.” Endo Ed has been specifically developed for Stony Brook undergraduates, but we hope this program can be adapted to help menstruators in other contexts.

Arm 1: Addressing the Knowledge Gap

Theoretical Foundation

Our needs assessment demonstrated that young menstruators are not learning about menstrual health (behavioral factor) and there is a lack of menstrual health educational opportunities in young menstruators’ lives (environmental). We identified a significant knowledge gap between what menstruators know about menstrual health and what they need to know to be able to find successful treatment. Young menstruators are not learning about menstrual health in schools, from their mothers, or from their doctors, so we seek to provide this information along an alternate route (Simpson et al., 2021). Our first goal is to increase young menstruators’ knowledge about worrisome menstrual symptoms and signs suggestive of endometriosis to encourage them to seek care. This assumes that people will seek more treatment for their menstrual issues if they understand normal and abnormal menstrual pain and the symptoms of endometriosis. While education is recognized to be insufficient to inspire behavior change on its own, it is still an essential first step of many behavior change theories (Corace & Garber, 2014). We seek to arm young menstruators with knowledge of their menstrual cycles to serve as a foundation for health-seeking behaviors such as visiting an endometriosis specialist. The most successful health education programs tailor information so that it is relevant to intended audience members and emphasize the pertinence of that information to them (Arlinghaus & Johnston, 2018).

There are several studies that support this theoretical basis as applied to menstrual pain and endometriosis. Khan et al. (2022) saw that menstrual education involving group lectures and discussions improved students’ knowledge of menstrual pain and its consequences. Abd Elrahim et al. (2022) not only found changes in endometriosis knowledge scores after an educational intervention but also saw statistically significant improvements in dysmenorrhea among girls who received the intervention. Bush et al. (2017) demonstrated that communities in New Zealand that had an endometriosis-focused educational curriculum had a greater proportion of menstruators under 25 years old attending gynecology clinic appointments.

Activities, Outputs, and Process Objectives

To address the menstrual health and endometriosis knowledge gap among our priority population, we will run an educational campaign across three different mediums: a classroom setting, social media, and digital and physical flyers. We hope that this variety of channels will cover the majority of members of our target community to have the greatest impact possible.

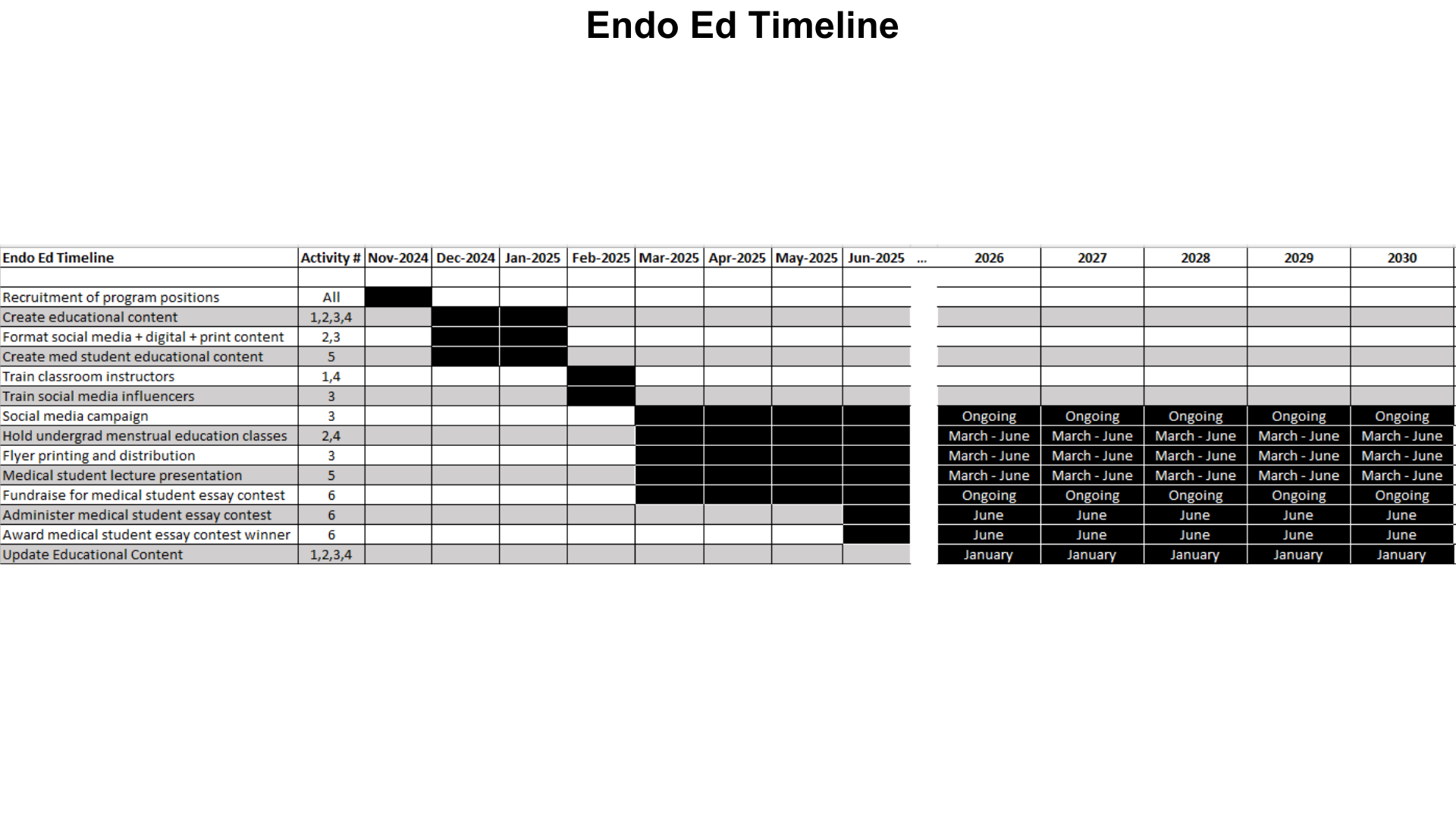

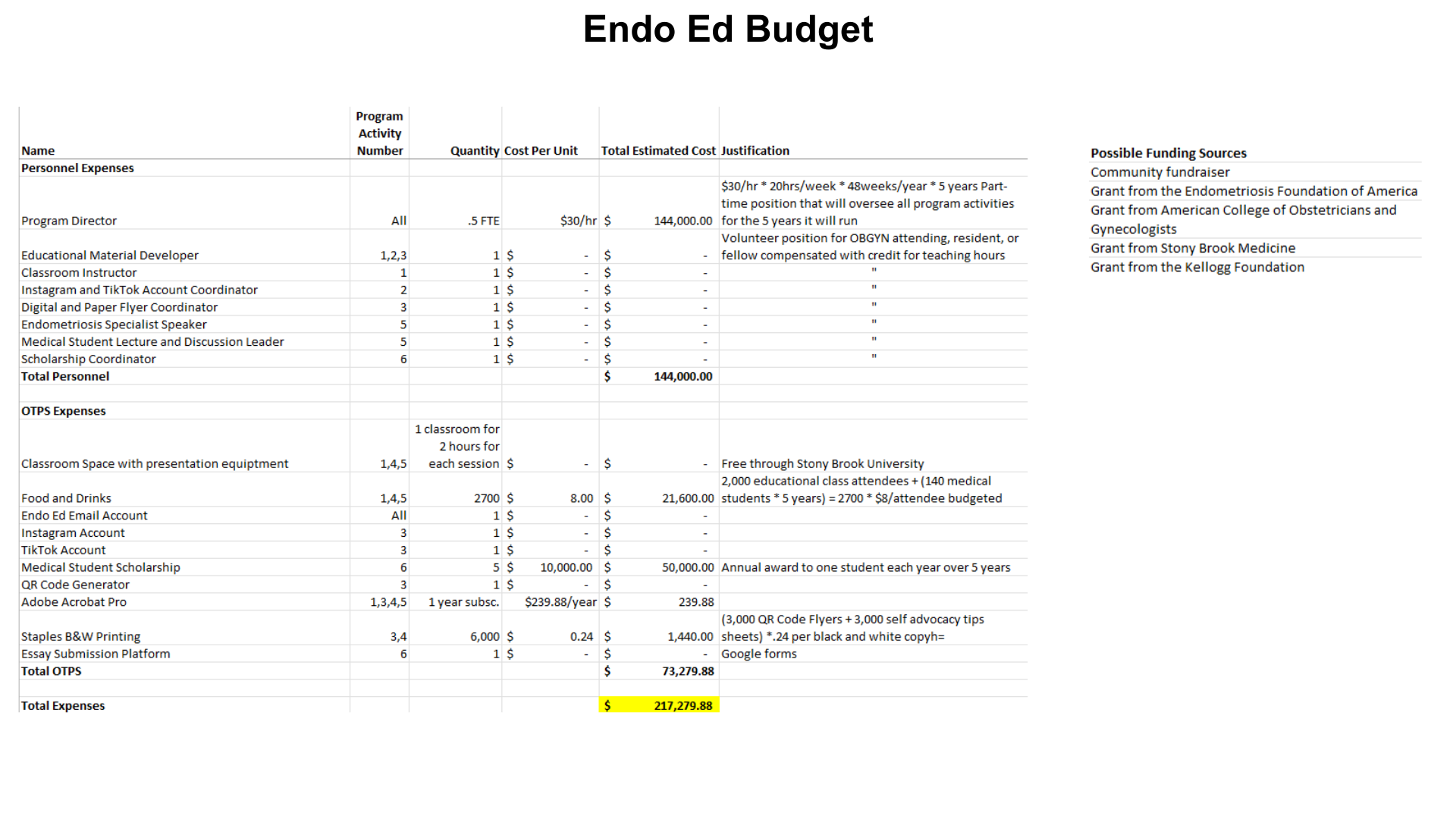

The Menstrual Health and Endometriosis class and discussion will be held in person ten times a year from March 2025 to June 2029. Our output for each class will be two 45-minute sessions with a lunch break in between, totaling a two-hour session. The first half will consist of a lecture on endometriosis and menstrual pain. See Appendix 8 for an outline of the curriculum. Lunch will be provided on-site, which we hope will encourage attendance. The second session will feature a discussion centered around giving space for menstruators to express their thoughts. This half will also address participant’s concerns and answer their questions. See Appendix 9 for an outline of this discussion. This activity leads to our first process objective: By June 2029, Endo Ed will deliver 2 hours of menstrual and endometriosis education to at least 2,000 college students at Stony Brook University as measured by attendance sheets from the 10 yearly sessions. Resources required will be classroom space equipped with technology for a presentation (provided by Stony Brook University), food and drink, educational materials including a PowerPoint presentation, and personnel. See Appendix 7 Budget. Program personnel will include an Educational Material Developer and a Classroom Instructor. See Appendix 5 Organizational Structure.

The second component of the educational arm will be a social media campaign aiming to disseminate knowledge about menstrual pain and endometriosis more widely across the campus community. Endo Ed TikTok and Instagram accounts will be created. The profiles will contain information about the Endo Ed to advertise classes but will also contain menstrual education resources. Each account will post twice per week: two short-form videos on TikTok and two Instagram posts. The output of this activity will be measured in terms of followers on each account. Our process objective will be: By June 2029, the Endo Ed Instagram will have 3,000 people engaging with Endo Ed through TikTok and Instagram, as measured by 3,000 followers on each platform. The resources required will be educational content, social media accounts (TikTok and Instagram), and personnel. See Appendix 7 Budget. Program personnel will include an Instagram and TikTok Account Coordinator. See Appendix 5 Organizational Structure.

The third and final component of the educational campaign will be paper flyers and a digital information packet. The digital information packet will contain much of the same content offered in the classroom session but formatted more succinctly for a general audience. This may include infographics and other visual representations of concepts. The digital information packet will also include tips for advocating for oneself in the doctor’s office, which will come from the self-advocacy training in the second arm of this program. A link to this PDF will be made available in the classes, on both social media accounts and through paper flyers handed out and posted around campus. The output of this activity will be the dissemination of physical flyers since there is no way to track the number of people who view the digital information packet as a PDF. The process objective that coincides with this activity is: by June 2029, Endo Ed will disseminate 3,000 flyers with the QR code to the menstrual education packet to menstruators throughout the Stony Brook Undergraduate campus. The resources required will include an Adobe Acrobat Pro PDF editor subscription, educational materials, a QR code generator, and paper flyers. See Appendix 7 Budget. Personnel will include the Digital/Paper Flyer Coordinator. See Appendix 5 for Endo Ed’s Organizational Structure.

Short- and Long-Term Outcomes and Learning/Behavioral Objectives

All three activities in the educational arm seek to achieve two short-term outcomes. The first outcome is increased knowledge about normal vs. abnormal menstrual symptoms and the signs of endometriosis. This information will be conveyed in the classroom sessions, the social media campaign, and the digital information packet. The learning objective that aligns with this outcome is: By June 2029, on an online survey, 75% of undergraduate menstruators at Stony Brook will be able to identify the normal duration of a period, normal amount of bleeding and pain, three indicators that there might be a menstrual problem, and two specific symptoms that may indicate endometriosis. The second expected outcome of the educational arm is to increase the likelihood that undergraduate menstruation will present to a doctor for their bothersome menstrual symptoms. This would demonstrate that the educational intervention was not only successful in increasing knowledge but also successful in promoting health-seeking behavior. This will be measured using the behavioral objective: by June 2029, on an online survey, the percentage of SBU students reporting that they visited a doctor for their menstrual symptoms will increase from a pre-test by 25%. The long-term outcomes that this intervention will contribute to are an increased number of Stony Brook undergraduates who report receiving satisfactory treatment of their menstrual pain/symptoms and an increased number of Stony Brook undergraduates who report having a positive interaction with their OBGYN for treatment of their menstrual symptoms.

Arm 2: Addressing Low Self-Efficacy

Theoretical Foundation

A salient behavioral factor contributing to untreated endometriosis is failing to visit a doctor for menstrual complaints, which is connected to the predisposing factor of having low self-efficacy in confronting a doctor and the reinforcing factor of having a prior negative experience with a doctor. Our community health assessment demonstrated that young menstruators may lack self-efficacy in advocating for their menstrual health. This is due in part because of the societal stigma surrounding menstruation and the perceived social norm that doctors always know best. That is why the goal for the second arm of Endo Ed is to increase young people’s self-efficacy in advocating for their reproductive health in the doctor’s office so they can have more productive visits. The assumption of this arm is that young menstruators will receive better treatment of menstrual disorders if they have higher self-efficacy in their ability to stand up to their doctor and advocate for them to take their symptoms seriously.

As previously stated, knowledge is often insufficient to produce behavior change alone, and self-efficacy is a component added to many behavior change theories to make them more complete representations of the antecedents of behavior change (Corace & Garber, 2014). The Risk Perception Attitude Theory (RPA), a framework most often employed in the context of health risks, combines the dimensions of perceived risk and self-efficacy to demonstrate that people are most motivated towards a health behavior when they have a perception of high personal risk and high self-efficacy to bring about change (Rimal & Real, 2003). Self-efficacy is one’s belief about one's own ability to achieve a specific goal; it is one's perception of one's sense of control over one's behavior. Self-efficacy not only varies from person to person but can vary within a person in different contexts. For instance, a woman may have high self-efficacy in advocating for her health in the primary care office about general health complaints but may have lower perceived self-efficacy in advocating for an OBGYN to address her menstrual concerns. Self-efficacy is known to be an important contributor to patients’ management of chronic conditions as interventions that increase self-efficacy can improve health outcomes (Farley, 2020). O’Hara et al. (2020) conducted a cross-sectional study of menstruators with endometriosis and found that having higher self-efficacy was not only associated with improved physical and psychological symptoms of endometriosis but also quality of life.

There are several ways to teach patients better self-advocacy skills, but we are choosing to use role-play situations in which students apply skills to advocate for themselves in a conversation with an OBGYN. Bandura’s Social Learning Theory (1977) emphasizes the importance of observational learning, in which an individual learns behaviors, skills, or attitudes by watching and then imitating others. Role-play has historically been used to teach therapeutic communication skills to those in therapy for mental health disorders (Rønning & Bjørkly, 2019). Though it has not been used in the context of helping patients learn advocacy skills or in any work in the context of menstruation or endometriosis, we are hopeful that the successes of role-playing in psychiatric therapy sessions will transfer to this context.

Activities, Outputs, and Process Objectives

To improve the self-efficacy of Stony Brook Undergraduate menstruators in advocating for themselves regarding their menstrual symptoms, we plan to hold a 30-minute self-advocacy training. This self-advocacy training will be held after the menstrual education classes. Students will learn how to advocate for their own health needs in the context of menstrual health. They will learn tips and strategies that they can employ during gynecology appointments to make it more likely that their physicians will take their concerns seriously. They will also role-play initiating conversations regarding menstrual health with their peers and employing strategies. The training will help increase their confidence and self-efficacy in getting what they need out of a doctor’s appointment. Appendix 10 for and outline of this training. The output of this activity will be ten, 30-minute self-advocacy training sessions each year. The process objective for the self-advocacy training is: By June 2029, Endo Ed will deliver 30 minutes of patient advocacy and self-advocacy training to at least 2,000 undergraduate students at Stony Brook University as measured by attendance sheets. The resources required are classroom space equipped with technology for a presentation (provided by Stony Brook University), self-advocacy training materials, and personnel. See Appendix 7 for Endo Ed’s Budget. Personnel will include the Educational Material Developer and the Classroom Instructor. See Appendix 5 for Endo Ed’s Organizational Structure.

Short- and Long-Term Outcomes and Learning/Behavioral Objectives

The short-term outcome of these training sessions is that young menstruators will feel more confident and self-efficacious regarding their ability to advocate for themselves in the doctor’s office. They should feel more comfortable discussing worrisome period symptoms with a doctor and demanding the treatment they deserve. This will help them combat any bias from their doctor in which they normalize period pain. This will be measured via the following learning objective: By June 2029, on a post-test or online survey, 50% of program attendees will report feeling more confident about seeing a doctor for the menstrual symptoms. Similar to the first arm, the long-term outcomes of the second intervention arm are and increased number of Stony Brook undergraduates who report receiving satisfactory treatment of their menstrual pain/symptoms and an increased number of students reporting having a positive interaction with their OBGYN for treatment of their menstrual symptoms.

Arm 3: Lack of Endometriosis Providers

Theoretical Foundation

The final arm of the Endo Ed program will attempt to address the shortage of competent endometriosis providers who practice evidence-based, patient-centered care for menstrual pain. This environmental problem not only encompasses a paucity of providers but also a lack of providers of diverse genders and cultures. This can be ameliorated by encouraging more medical students to pursue OBGYN as a specialty and creating financial incentives for students from all backgrounds to pursue sub-specialty training in gynecological surgery and advanced training in endometriosis care. Therefore, the third goal of Endo Ed is to increase the number of well-rounded endometriosis specialists performing patient-centered care. One assumption that underlies this intervention is that increasing the number and diversity of providers will increase the number of menstruators who seek a visit for endometriosis. Data supports that there is a lack of providers who can provide essential endometriosis care, and it is reasonable that increasing the number available will be one way to increase the number of menstruators who are treated (As-Sanie et al., 2019). Additionally, research shows that patient-physician racial and gender concordance can increase use of healthcare (Saha et al., 1999). Therefore, increasing the number and diversity of endometriosis providers may help menstruators access more treatment for their menstrual pain and symptoms. Another assumption is that a financial incentive will encourage more medical students to consider OBGYN training and encourage more to practice endometriosis care. The literature supports that scholarship and loan forgiveness programs encourage medical students to practice primary care in underserved areas (Geletko et al., 2014). While there has been no evidence of the use of such a scholarship program in gynecology, it is reasonable to think that financial incentives may entice more students to specialize in this field. It is also reasonable to expect that more medical students will want to go into OBGYN and endometriosis care if they understand the scope of the menstrual pain crisis and there is a financial incentive to do so.

Activities, Outputs, and Process Objectives

There will be two activities in this arm of Endo Ed. The first will be an endometriosis-specific lecture to all second-year medical students as part of their pre-clinical curriculum, and the second will be an essay competition with a scholarship for fourth-year medical students attending Stony Brook University’s Renaissance School of Medicine who are applying to OBGYN residencies. The endometriosis-specific lecture will be a two-hour-long information session and discussion. This will include not only the pathophysiology and treatment of endometriosis but also how menstrual pain is a critical issue affecting menstruators today. This activity’s output will be an annual two-hour long session on endometriosis for second-year medical students in their Reproduction and Endocrinology course. The process objective for this output is: By June 2029, Endo Ed will deliver 1 hour of endometriosis education to five classes of 2nd-year med students (~140/year). The aim of this session is to not only inform students but also inspire them to take part in changing the menstrual health landscape for menstruators. This lecture will require educational materials, an endometriosis specialist, and a lecture hall equipped with presentation technology (provided by Stony Brook University). See Appendix 7 Budget. The personnel involved in this intervention will be an Endometriosis Specialist Speaker and the Medical Student Lecture and Discussion Leader. They will consult with the Stony Brook Medical School Reproduction and Endocrinology Course Director. See Appendix 5 Organizational Structure. The outline of this presentation can be found in Appendix 11.

The second activity will be a scholarship program. We will hold an annual essay contest for 4th-year medical students attending Stony Brook University’s Renaissance School of Medicine applying to OBGYN residencies with a financial prize. They will be asked to address their interest in the field, how they will advocate for patients experiencing menstrual pain and endometriosis, and if they are interested in sub-specializing in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, the field that most often treats endometriosis. The Essay prompt can be found in Appendix 12. One student will be picked as a winner annually to receive a one-time $10,000 scholarship, contingent on their matching into OBGYN residency. The process objective for this activity is: Each academic year for the next 5 years, Endo Ed will hold an endometriosis essay contest for 4th-year students attending Stony Brook University’s Renaissance School of Medicine who are applying to OBGYN residencies and award a $10,000 scholarship to the winner. The resources needed will include a platform for the essay contest (Google Forms) and the annual scholarship money. See Appendix 7 Budget. There will be a Scholarship Coordinator position. See Appendix 5 Organizational Chart.

Short-Term Outcomes and Learning/Behavioral Objectives

One expected short-term outcome for the medical student arm of Endo Ed is that more students will be interested in specializing in OBGYN, and there will be increased consideration for subspecializing in endometriosis care. The learning objective for the medical student endometriosis lecture is that each year after the lecture, 90% of student attendees will agree that endometriosis must be addressed as a public health issue. The behavioral objective for the scholarship program is that by June 2029, there will be 20% more Stony Brook Medical Students going into OBGYN than in 2024. The long-term outcome is that there will be an increased number and quality of OBGYN endometriosis specialists from diverse backgrounds.

Impact

The overall goal of Endo Ed is that the three intervention arms will improve menstruation for students across the Stony Brook University community. Specifically, we aspire to decrease the prevalence of undiagnosed severe menstrual pain and inadequately treated endometriosis and decrease the quality-of-life burden of menstrual pain. These impacts will be measured by the achievement of three impact objectives: By June 2029, on an online survey, 50% more SBU students will report that they received satisfactory endometriosis treatment; By June 2029, 50% fewer SBU students will report missing school/work because of their periods; By June 2045, there will be 10% more endometriosis specialists on Long Island. We hope that the impact of Endo Ed will help fulfill the mission of helping people have happier, healthier periods.

Addressing Cultural Competency

Endo Ed recognizes the essential need to practice cultural humility when intervening in any community, and we will take steps to ensure that our program considers the cultural context of our population. One of the challenges we will face is that our priority population is diverse; Stony Brook has a racially and ethnically diverse student body that comes from across the US and around the world (US News and World Report, n.d.). Thus, the first iteration of Endo Ed will not be tailored to one demographic or cultural group, but we will remain open to the diverse perspectives and experiences of our participants throughout the program's implementation. For instance, during our classroom discussion sessions, we will create space for menstruators to reflect on their experiences of societal attitudes towards menstruation, which may vary based on their cultural background. Menstruation is taboo and even shameful in many cultures, and some menstruators may not want to discuss their personal experiences (McHugh, 2020). We also recognize that many Stony Brook Undergraduates come to the US from countries abroad, which may have more explicit discrimination against menstruators (US News and World Report, n.d.). Thus, we will keep space for participants to discuss their feelings and opinions but will not create pressure to do so.

We hope that the general population of Stony Brook University undergraduates enjoy our classes and find the education and self-advocacy training offered by Endo Ed helpful. We will appreciate feedback from our diverse body of participants and will consider how their cultural differences inform their experiences in the program. We will consider tailoring Endo Ed to better meet the needs of specific cultural groups if they become evident during the implementation.

One demographic that we want to tailor Endo Ed for further is transgender and gender-diverse individuals. While the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recognizes the importance of inclusive and affirming gynecological care for gender-diverse patients and makes recommendations on fertility, pregnancy, contraceptive, abortion care, and preventive screening in this population, endometriosis care for transgender patients is not mentioned once (Health care for transgender and gender diverse individuals, n.d.). The Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health has guidelines for “respectful menstruation-related care to transgender and gender non-binary patient populations,” but they, too, fail to address endometriosis (Recommendations for Providing Respectful Menstruation-Related Care to Transgender and Gender Non-Binary Patient Populations, n.d.). While Endo Ed attempts to maintain inclusivity in its use of “menstruators,” which is a common term for girls, women, transgender men, non-binary people, and all others who also menstruate in academia, we recognize that our program can and should expand beyond just inclusive language (Babbar et al., 2023). We hope to engage with members of the Stony Brook University community who identify as gender diverse community to better tailor Endo Ed to their needs and ensure that anyone impacted by menstruation is included.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2: Data Collection Instrument- Qualtrics Undergraduate Menstrual Health Questionnaire https://stonybrookuniversity.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_5hbN0WwUbrcvGvk

Do you menstruate (get a period)?

- Yes

- No

The following questions are based on your knowledge of menstrual/period health

1 Do you know how long a period should typically last?

- Yes

- Maybe

- No

2 Do you know how much bleeding in one day is considered normal?

- Yes

- Maybe

- No

3 Do you know the level of pain that is normal to have when you're on your period?

- Yes

- Maybe

- No

4 Is it normal for a person to miss a day of school/work every month because of their period?

- Yes

- Maybe

- No

5 Do you know if it's normal for someone to bleed clots of blood on their period?

- Yes, it's normal

- It depends, there may be a problem

- No, it means there is a problem

6 Do you know signs that indicate when someone should see a doctor about their period?

- Yes

- Maybe

- No

7 Do you know how to recognize symptoms of endometriosis?

- Yes, I know the symptoms

- I've heard of it, but I don't know the symptoms

- No, I've never heard of it

The rest of the questions ask about your personal experience with your period

8 How many days do you bleed on your period?

- 1 day

- 2 days

- 3 days

- 4 days

- 5 days

- 6 days

- 7 days

- More than 7 days

9 How many tampons or pads do you use daily on the heaviest day of your period?

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- More than 6

- I don't know

10 How would you rate the worst pain you have during your period?

- No pain 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- Worst pain ever 10

11 Do you ever leak blood onto your clothes or bed sheets, even when you are wearing a tampon or pad?

- Rarely or never

- Occasionally, but not every period

- Yes, probably once every period

- Yes, multiple times a month

12 Do your period symptoms cause you anxiety?

- Rarely or never

- Occasionally

- Often

- Always

13 Are you ever embarrassed about your period symptoms?

- Rarely or never

- Occasionally

- Often

- Always

14 Do you ever worry about bleeding onto your clothes?

- Rarely or never

- Occasionally

- Often

- Always

15 Are you worried about your symptoms getting worse?

- Yes

- No

16 Do you ever miss class or work due to period pain or other symptoms?

- Rarely or never

- Occasionally

- Often

- Always

17 Do you ever miss social events (hanging out with friends, parties, etc.) because of your period?

- Rarely or never

- Occasionally

- Often

- Always

18 Do you have problems with your relationships because of your period?

- Rarely or never

- Occasionally

- Often

- Always

19 Have you seen a doctor about your period symptoms?

- Yes

- No

20 Do you feel that your doctor took your concerns seriously?

- Yes

- Maybe

- No

21 Are you satisfied with the medical treatment you got for your pain?

- Yes

- Maybe

- No

22 What treatments did your doctor give you? (check all that apply)

- Tylenol or Advil (acetaminophen or ibuprofen)

- Birth control pills

- IUD

- Surgery

- Other

- My doctor didn't offer any treatments

23 Did your doctor give you a diagnosis for your period symptoms?

- Yes

- No

24 What was your diagnosis? _____________________________________

Do you have any questions, concerns, or comments?__________________________

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Appendix 5

Appendix 6

Appendix 7

Appendix 8 – Undergraduate Class Curriculum Outline

- Period pain and symptoms: what’s normal vs abnormal?

- Definition of endometriosis

- Symptoms of endometriosis

- Consequences of untreated endometriosis

- Treatment of endometriosis

- Why endometriosis treatment in the US is suboptimal

Appendix 9 – Undergraduate Class Discussion Questions

- How do your menstrual symptoms and pain impact your daily life?

- What have your experiences been when trying to get your menstrual pain addressed in the doctor’s office?

- What can health professionals do better?

- What are some ways you can advocate for yourself? What do you need to feel more confident advocating for yourself in the doctor’s office for the treatment of your menstrual pain?

Appendix 10 – Self-Advocacy Training Outline

- What is self-advocacy, and how can it help you get your needs met in the doctor’s office?

- Tips

- Make a plan before your appointment

- Be honest about how your symptoms affect your life and explain your point of view

- Ask questions

- Keep detailed records

- Ask the doctor to explain their decisions and document them in the chart

- Bring a friend or a family member

- Don’t be afraid of questioning your doctor

- If your doctor says they can’t help you, ask them to help you find someone who can

- How to find a doctor who will listen to you

- Roleplay exercise

- One person takes on the role of an OBGYN, and the other is a patient experiencing severe menstrual pain

- Choose whether this is the patient’s first time addressing this issue or if it has been brought up before

- Use some of the strategies you learned to get this doctor to take your pain seriously

Appendix 11 – Medical Student Class Outline

- Normal vs pathological menstruation

- Definition of endometriosis and clinical symptoms

- Impact of endometriosis and epidemiology

- Etiology, pathophysiology, and pathology

- Complications and sequelae

- Diagnostic workup

- Treatment options

- Addressing menstrual pain as a public health issue

- Questions and Discussion

- If applicable to you, how do your menstrual symptoms and pain impact your daily life, or how does a loved one’s experience impact them?

- How can you, as a future physician, approach menstrual pain as a public health issue?

- How can you be an advocate for patients living with endometriosis?

Appendix 12 – Medical Student Essay Competition Eligibility Criteria and Prompt

Eligibility Criteria

- You must be a 4th-year medical student at the Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine

- You must be in good academic standing as per the Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine Dean’s Office

- You must have completed the USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 exams by the time of your submission, though scores aren’t necessary

- You must be applying for OBGYN residency in the United States during the current application cycle and submitting applications to at least two hospitals on Long Island

- You should have demonstrated a passion for reproductive health during your medical education, including advocacy work, clinical volunteering, and research experience

- You must have one letter of recommendation from an OBGYN faculty member at Stony Brook University Hospital explaining how you are a strong residency candidate and a deserving candidate for this scholarship program

Please address the following in an essay of no more than 1,000 words:

- Please discuss why you are applying for OBGYN residency and how your personal and professional experiences have led you to the field. What are your career aspirations for the next 10 years? What are your sub-specialty interests? Where do you see yourself working (geographic location, community vs academic setting, hospital vs outpatient setting)? What patient populations do you want to serve?

- How is menstrual pain a public health issue? Please, how do you plan to use your career to address menstrual pain as a public health issue? How will you be an advocate for patients living with endometriosis?

Please attach your CV to your submission.

References

Abd Elrahim, A. H., Abdelnaem, S. A., Abuzaid, O. N., & Allah, M. F. H. (2022). Educational intervention and referral for early detection of endometriosis among technical secondary schools students. Egyptian Nursing Journal, 19(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.4103/enj.en... In Egypt

Arlinghaus, K. R., & Johnston, C. A. (2018). Advocating for behavior change with education. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 12(2), 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827617745479

As-Sanie, S., Black, R., Giudice, L. C., Gray Valbrun, T., Gupta, J., Jones, B., Laufer, M. R., Milspaw, A. T., Missmer, S. A., Norman, A., Taylor, R. N., Wallace, K., Williams, Z., Yong, P. J., & Nebel, R. A. (2019). Assessing research gaps and unmet needs in endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 221(2), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.033

Babbar, K., Martin, J., Varanasi, P., & Avendaño, I. (2023). Inclusion means everyone: standing up for transgender and non-binary individuals who menstruate worldwide. The Lancet Regional Health. Southeast Asia, 13(100177), 100177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100177

Corace, K., & Garber, G. (2014). When knowledge is not enough: changing behavior to change vaccination results [Review of When knowledge is not enough: changing behavior to change vaccination results]. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 10(9), 2623–2624. Informa UK Limited. https://doi.org/10.4161/21645515.2014.970076

Dysmenorrhea and Endometriosis in the Adolescent. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2024, from https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/12/dysmenorrhea-and-endometriosis-in-the-adolescent

Ellis, K., Munro, D., & Clarke, J. (2022). Endometriosis is undervalued: A call to action. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 3, 902371. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.902371

Endometriosis, Foundation, EndoFound, endometriosis Foundation of America. (2010, July 22). Endometriosis : Causes - Symptoms - Diagnosis - and Treatment; Endometriosis Foundation of America. https://www.endofound.org/

Farley, H. (2020). Promoting self-efficacy in patients with chronic disease beyond traditional education: A literature review. Nursing Open, 7(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.382

Flickr, F. us on. (n.d.). What are the treatments for endometriosis? Https://www.nichd.nih.gov/. Retrieved December 6, 2024, from https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/endometri/conditioninfo/treatment

Fryer, J., Mason-Jones, A. J., & Woodward, A. (2024). Understanding diagnostic delay for endometriosis: a scoping review. In medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.08.24300988

Geletko, K. W., Brooks, R. G., Hunt, A., & Beitsch, L. M. (2014). State scholarship and loan forgiveness programs in the United States: Forgotten driver of access to health care in underserved areas. Health, 06(15), 1994–2003. https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2014.615234

Hansen, K. A., & Eyster, K. M. (2010). Genetics and genomics of endometriosis. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 53(2), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181db7ca1

Health care for transgender and gender diverse individuals. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2024, from https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2021/03/health-care-for-transgender-and-gender-diverse-individuals

Hoffman, A. J. (2013). Enhancing self-efficacy for optimized patient outcomes through the theory of symptom self-management. Cancer Nursing, 36(1), E16-26. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824a730a

Hudson, N. (2022). The missed disease? Endometriosis as an example of “undone science.” Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online, 14, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbms.2021.07.003

L W Green, Gielen, A. C., Ottoson, J. M., Peterson, D. V., & Kreuter, M. W.}. (2022). Health Program Planning, Implementation, Evaluation: Creating Behavioral, Environmental, Policy Change. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Leung, F.-H., & Savithiri, R. (2009). Spotlight on focus groups. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 55(2), 218–219. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19221085

Long, M., Frederiksen, B., Ranji, U., Diep, K., & Salganicoff, A. (2023, February 22). Women’s experiences with provider communication and interactions in health care settings: Findings from the 2022 KFF women’s Health Survey. KFF. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/womens-experiences-with-provider-communication-interactions-health-care-settings-findings-from-2022-kff-womens-health-survey/

López, C. L., Wilson, M. D., Hou, M. Y., & Chen, M. J. (2021). Racial and ethnic diversity among obstetrics and gynecology, surgical, and nonsurgical residents in the US from 2014 to 2019. JAMA Network Open, 4(5), e219219. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.9219

Mann, J., Shuster, J., & Moawad, N. (2013). Attributes and barriers to care of pelvic pain in university women. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, 20(6), 811–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2013.05.003

McHugh, M. C. (2020). Menstrual shame: Exploring the role of ‘menstrual moaning.’ In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies (pp. 409–422). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_32

Moradi, M., Parker, M., Sneddon, A., Lopez, V., & Ellwood, D. (2019). The Endometriosis Impact Questionnaire (EIQ): a tool to measure the long-term impact of endometriosis on different aspects of women’s lives. BMC Women’s Health, 19(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0762-x

New York state department of health recognizes endometriosis awareness month. (n.d.). Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://www.health.ny.gov/press/releases/2024/2024-03-21_endometriosis.htm

Nirgianakis, K., Vaineau, C., Agliati, L., McKinnon, B., Gasparri, M. L., & Mueller, M. D. (2021). Risk factors for non-response and discontinuation of Dienogest in endometriosis patients: A cohort study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 100(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13969

O’Hara, R., Rowe, H., & Fisher, J. (2021). Self-management factors associated with quality of life among women with endometriosis: a cross-sectional Australian survey. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 36(3), 647–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaa330

O’Laughlin, D. J., Strelow, B., Fellows, N., Kelsey, E., Peters, S., Stevens, J., & Tweedy, J. (2021). Addressing anxiety and fear during the female pelvic examination. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 12, 2150132721992195. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132721992195

Olowojesiku, R., Shim, D. J., Moppins, B., Park, D., Patterson, J. O., Schoenl, S. A., Gaines, J. K., Sperr, E. V., & Baldwin, A. (2021). Menstrual experience of adolescents in the USA: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open, 11(2), e040511. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040511

Olson, M. M., Alhelou, N., Kavattur, P. S., Rountree, L., & Winkler, I. T. (2022). The persistent power of stigma: A critical review of policy initiatives to break the menstrual silence and advance menstrual literacy. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(7), e0000070. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000070

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Parasar, P., Ozcan, P., & Terry, K. L. (2017). Endometriosis: Epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Current Obstetrics and Gynecology Reports, 6(1), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-017-0187-1

Pontoppidan, K., Olovsson, M., & Grundström, H. (2023). Clinical factors associated with quality of life among women with endometriosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health, 23(1), 551. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02694-5

Recommendations for Providing Respectful Menstruation-Related Care to Transgender and Gender Non-Binary Patient Populations. (n.d.). Mailman School of Public Health. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/file/8014/download?token=T0BCryiO

Recommendations for Providing Respectful Menstruation-Related Care to Transgender and Gender Non-Binary Patient Populations. (n.d.). Mailman School of Public Health. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/file/8014/download?token=T0BCryiO

Regional Health-Americas, T. L. (2022). Menstrual health: a neglected public health problem. Lancet Regional Health. Americas, 15(100399), 100399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100399

Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2003). Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change. Human Communication Research, 29(3), 370–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2003.tb00844.x

Rønning, S. B., & Bjørkly, S. (2019). The use of clinical role-play and reflection in learning therapeutic communication skills in mental health education: an integrative review. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 10, 415–425. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S202115

Saha, S., Komaromy, M., Koepsell, T. D., & Bindman, A. B. (1999). Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159(9), 997–1004. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.9.997

Saha, S., Komaromy, M., Koepsell, T. D., & Bindman, A. B. (1999). Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159(9), 997–1004. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.9.997

Shalowitz, D. I., Tucker-Edmonds, B., Marshall, M.-F., & White, A. (2022). Responding to patient requests for women obstetrician-gynecologists. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 226(5), 678–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.015

Simpson, C. N., Lomiguen, C. M., & Chin, J. (2021). Combating diagnostic delay of endometriosis in adolescents via educational awareness: A systematic review. Cureus, 13(5), e15143. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.15143

State of sex education in USA. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2024, from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/for-educators/whats-state-sex-education-us

Stony Brook Office of Communications. (n.d.). Stony Brook fast facts. Retrieved December 6, 2024, from https://www.stonybrook.edu/about/facts-and-rankings/

Stony Brook University, NY. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2024, from https://datausa.io/profile/geo/stony-brook-university-ny/

Surrey, E., Soliman, A. M., Trenz, H., Blauer-Peterson, C., & Sluis, A. (2020). Impact of endometriosis diagnostic delays on healthcare resource utilization and costs. Advances in Therapy, 37(3), 1087–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01215-x

Takeshita, J., Wang, S., Loren, A. W., Mitra, N., Shults, J., Shin, D. B., & Sawinski, D. L. (2020). Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Network Open, 3(11), e2024583. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583

UNICEF. (2024). 10 Fast Facts: Menstrual health in schools. Global UNICEF for Every Child. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/10-fast-facts-menstrual-health-schools

US News and World Report. (n.d.). Stony Brook University--SUNY. US News and World Report. Retrieved November 11, 2024, from https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/stony-brook-suny-2838#:~:text=It%20has%20a%20total%20undergraduate,campus%20size%20is%201%2C454%20acres.

US News. (2024). Stony Brook University--SUNY Student Life. https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/stony-brook-suny-2838/student-life

Vannuccini, S., Rossi, E., Cassioli, E., Cirone, D., Castellini, G., Ricca, V., & Petraglia, F. (2021). Menstrual Distress Questionnaire (MEDI-Q): a new tool to assess menstruation-related distress. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 43(6), 1107–1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.08.029

Wiggleton-Little, J. (2024). “Just” a painful period: A philosophical perspective review of the dismissal of menstrual pain. Women’s Health (London, England), 20, 17455057241255646. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455057241255646

Wijeratne, D., Gibson, J. F. E., Fiander, A., Rafii-Tabar, E., & Thakar, R. (2024). The global burden of disease due to benign gynecological conditions: A call to action. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 164(3), 1151–1159. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.15211

Zannoni, L., Giorgi, M., Spagnolo, E., Montanari, G., Villa, G., & Seracchioli, R. (2014). Dysmenorrhea, absenteeism from school, and symptoms suspicious for endometriosis in adolescents. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 27(5), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpa

Post a comment