Underestimated Hazard: Homicide in Pregnancy

Briefing Outline

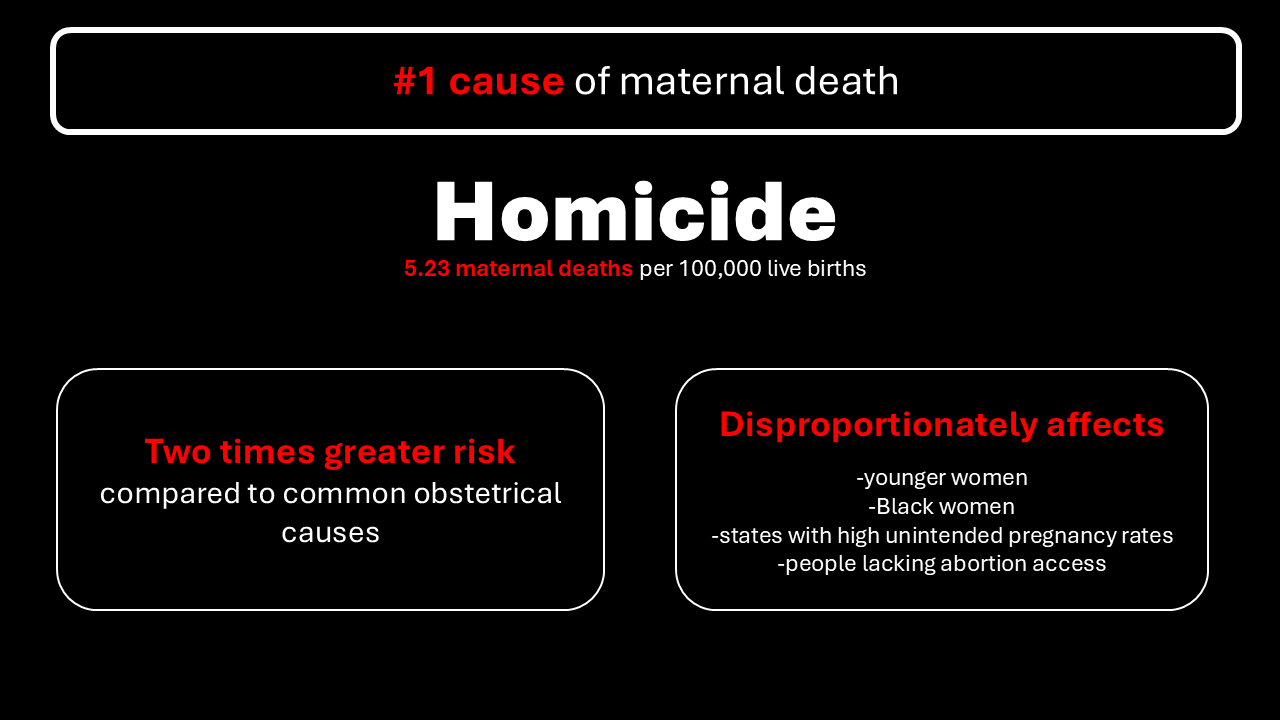

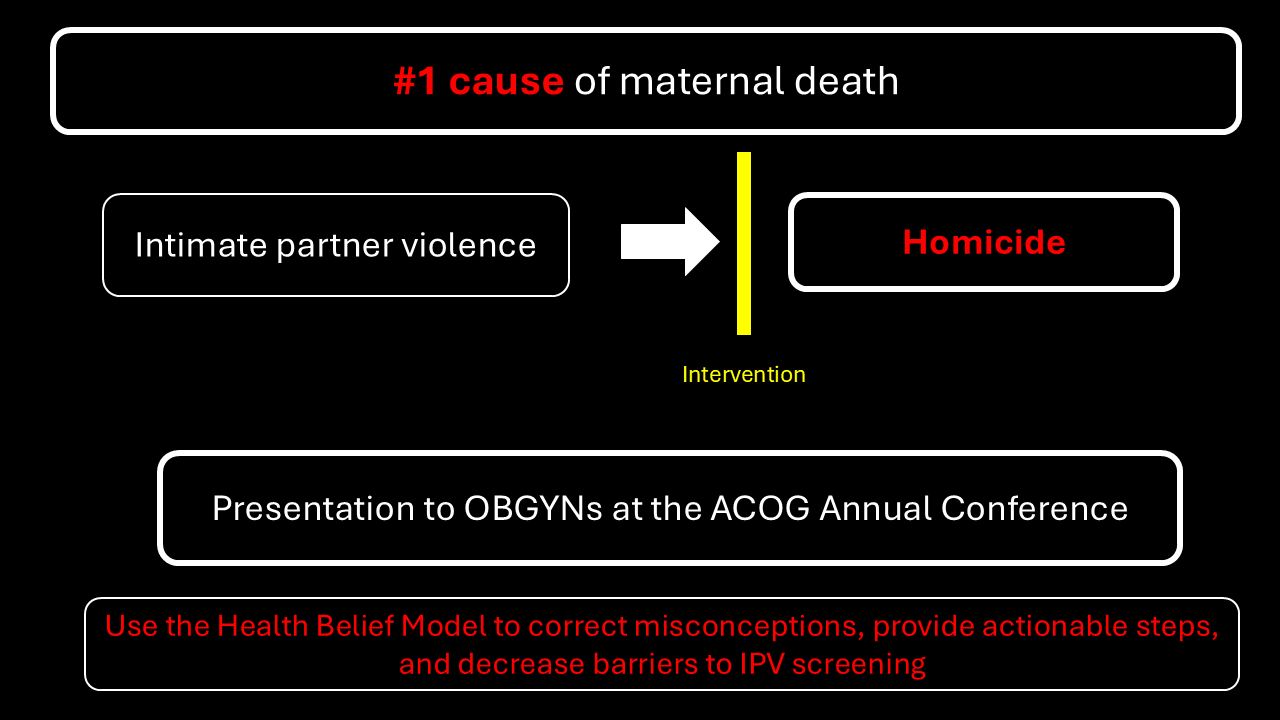

The United States has the highest maternal mortality of all high-income countries, yet the leading cause of these deaths is largely unrecognized (Gunja et al., 2024). Homicide is the number one killer during pregnancy and in the first 42 days postpartum, causing an alarming 5.23 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births annually in the US (Keegan et al., 2024). Homicide exceeds all obstetrical causes of death by greater than twofold, and a woman is twice as likely to be murdered while pregnant than when not (Modest et al., 2022). The burden of maternal homicide is not a new phenomenon, as decades of data demonstrate that the most significant risk to a pregnant woman is not a what but a who (Campbell et al., 2021; Roush, 2023). This problem is only worsening, as maternal homicides rose 32.4% from 2019 to 2020 (Wallace, 2022).

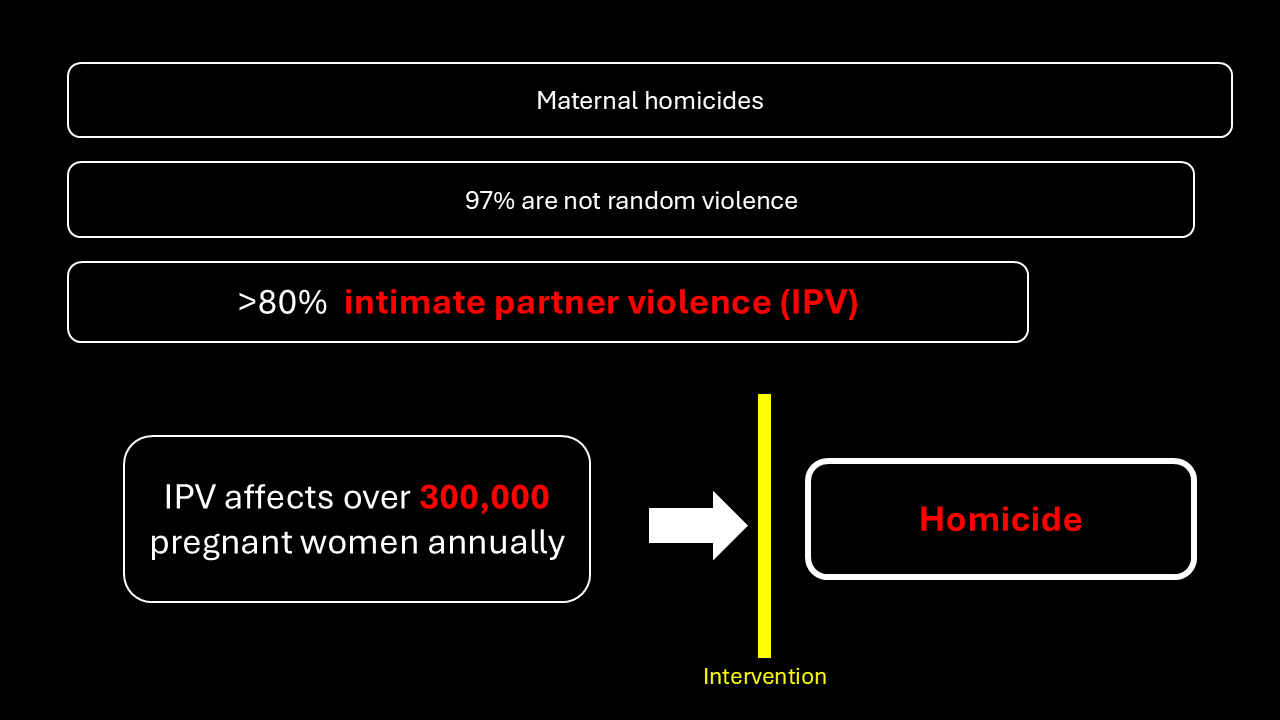

The disturbing trend of maternal homicide is multifactorial, but risk factor one stands out among the rest. Studies indicate that 97% of peripartum homicides are not acts of random violence, and as many as 80% are the culmination of intimate partner violence (IPV) (Keegan et al., 2024; Roush, 2023). Furthermore, homicide is rarely the first instance of abuse in a relationship. Up to 28% of expectant mothers experience physical violence, and an unknown number endure emotional abuse (Szewczyk et al., 2024). Pregnancy can be a stressful time for couples, and this stress far too often manifests itself as the escalation of IPV. The US has a greater prevalence of IPV in pregnancy compared to similar countries, which may be explained by the high rates of unintended pregnancy, lack of access to abortion, and easy access to firearms, all of which increase homicide risk (Lawn & Koenen, 2022). The burden of IPV and maternal homicide disproportionately affects some more than others. For instance, Black pregnant women, younger mothers, and women of low socioeconomic status are at a disproportionately higher risk of being murdered (M. Wallace et al., 2021).

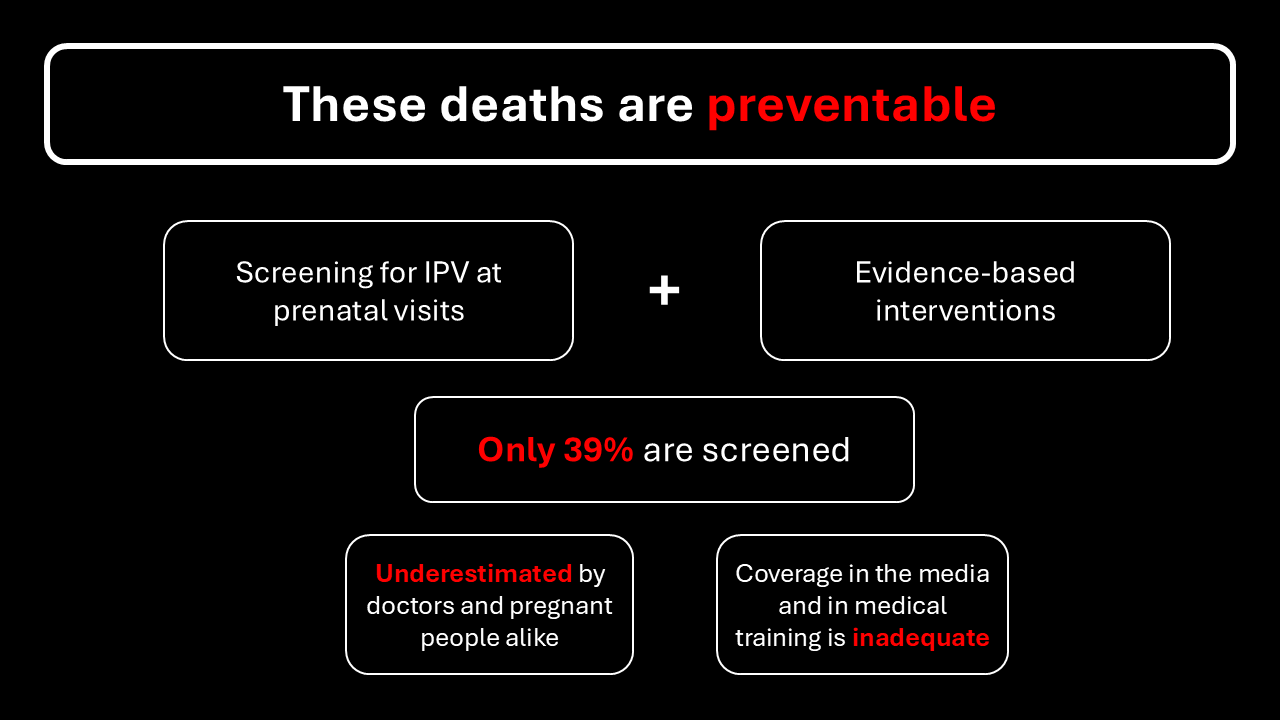

Despite being the most significant risk women face during pregnancy, little attention is paid to homicide in this population. Studies show that women and healthcare providers alike underestimate the risk of peripartum homicide, and they tend to view scenarios involving preeclampsia and vaginal bleeding as posing a higher risk than IPV (Lee et al., 2019; Procentese et al., 2019). Even most obstetricians are surprised to learn the impact of intimate partner violence (Clements et al., 2011; Roelens et al., 2009). Ample research and interventions address the leading obstetrical causes of maternal mortality but much less is known about preventing homicide, which is a more significant burden (Campbell et al., 2021; Lawn & Koenen, 2022). Additionally, media coverage of maternal homicide is inadequate, sporadically peaking with sensationalized stories (Clements et al., 2011). Efforts to mitigate the risk of peripartum homicide center around screening for IPV as they are so strongly associated. While the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening for IPV at prenatal visits based on the results of numerous studies, the rates of adherence are dismal; only 39% of women are screened (Clements et al., 2011; M. E. Wallace, 2022; Keegan et al., 2024)

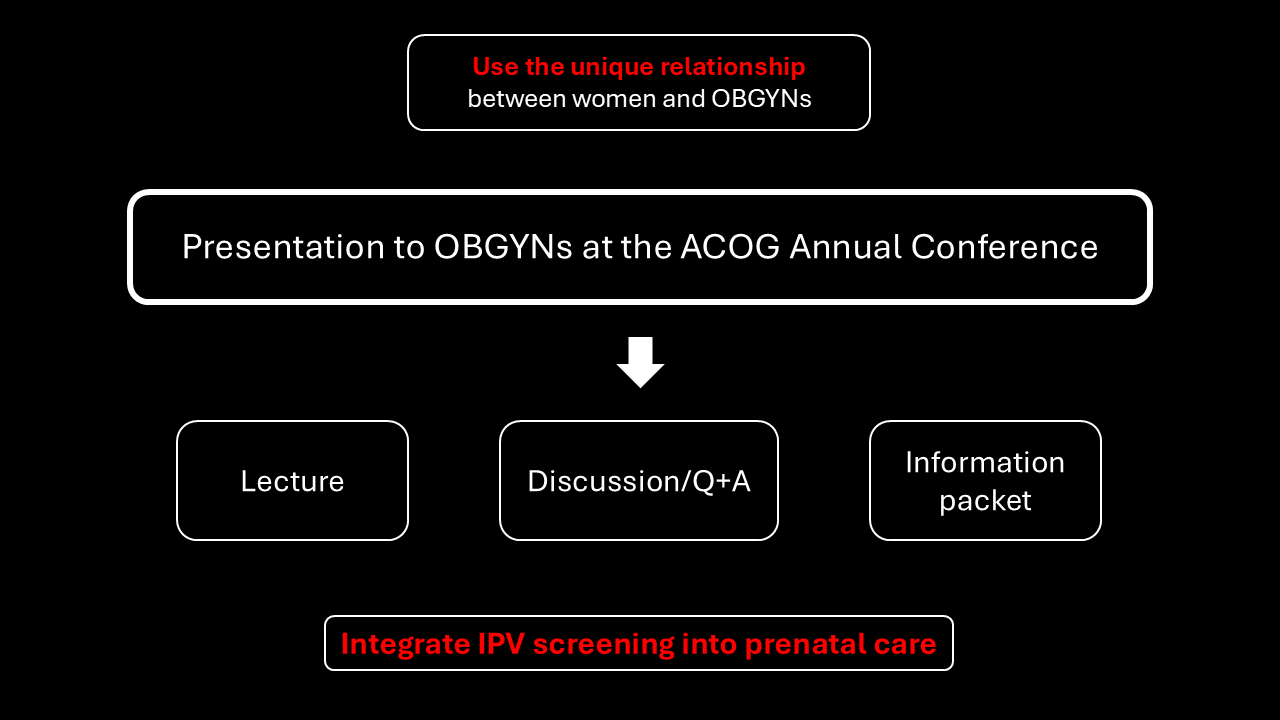

While it is important that expectant mothers are aware of their risk of homicide, we must recognize the complexity of IPV and cannot place the onus for prevention on these victims. OBGYNs develop close, longitudinal relationships with their patients, therefore, they are in a unique position to discuss IPV with their patients. That is why I propose that a communication intervention about maternal homicide must target physicians, as they’re best capable of addressing the underestimated hazard of maternal homicide.

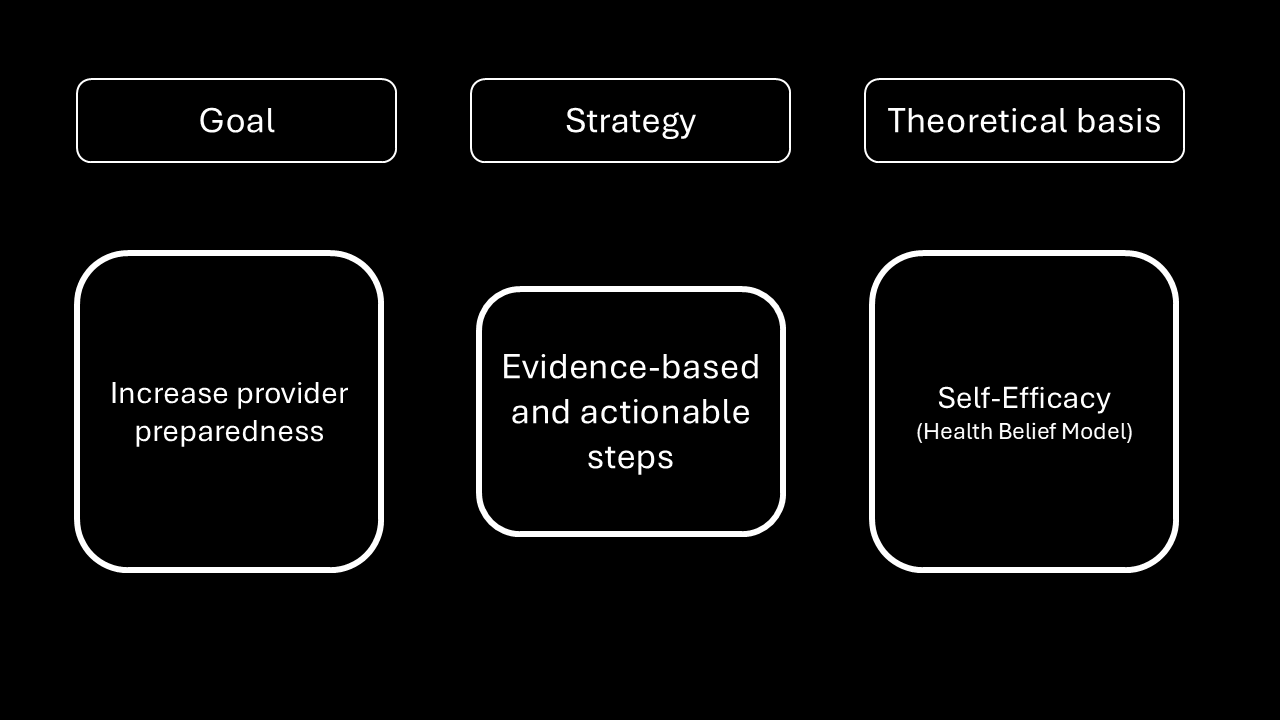

There is a paucity of research on how to best communicate maternal homicide to OBGYNs and inspire them to initiate intimate partner violence screening. One review found that programs aiming to increase the rates of IPV screening in the healthcare setting were most successful when they considered provider self-efficacy, which is their belief about their ability to implement screening (O’Campo et al., 2011). The Health Belief Model posits that self-efficacy is an essential variable that can promote behavior change (National Cancer Institute, 2005). Unfortunately, research shows that a significant barrier to IPV screening is doctors’ lack of confidence in their ability to identify and support victims (Ibrahim et al., 2021).

It is established that effective communication is a prerequisite to changing how physicians practice (Gesme & Wiseman, 2010). I believe that the most effective communication strategy to deliver a message about maternal IPV and homicide to OBGYNs would be a presentation and discussion at a conference. Because communicator credibility can affect persuasiveness, an expert in maternal IPV and homicide should facilitate the session, as they would be perceived highly in both expertise and trustworthiness (O’Keefe, 2002). The session should be a lecture-style presentation with ample time for questions and discussion, as this is the most familiar format at conferences. To reach the widest audience and ensure that physicians can reference the talk materials later, an information packet will be distributed in paper and electronic formats to both attendees and the conference email list.

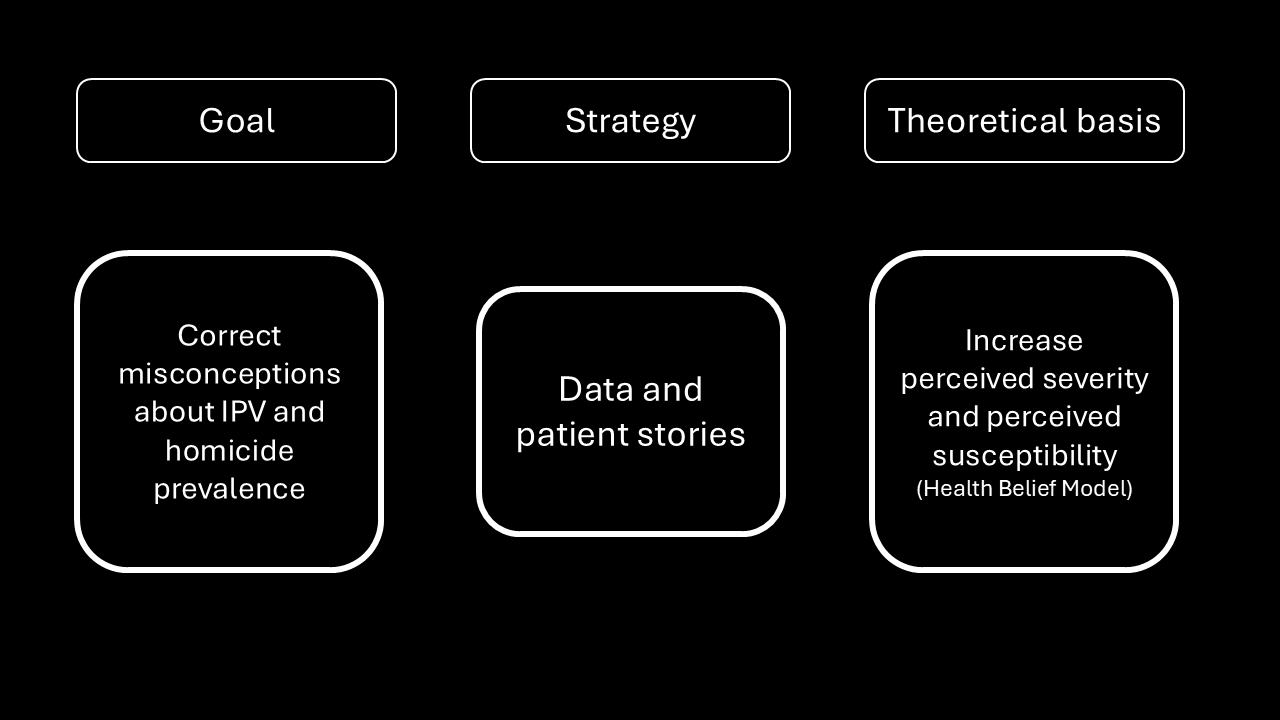

One goal of this talk is to increase OBGYN’s perceived susceptibility of their patients to IPV and homicide and increase their sense of the severity of IPV. Perceived susceptibility and perceived severity are core concepts in the Health Belief Model, and a higher level of these dimensions would motivate doctors to implement IPV screening to prevent homicide (National Cancer Institute, 2005). The talk will include data about the prevalence and burden of IPV in pregnancy, as well as patient stories, to ensure that doctors are aware of how IPV and homicide affect expectant mothers. Many physicians likely fall victim to the availability heuristic in that they imagine the leading causes of maternal death are high blood pressure and bleeding, as these easily come to mind based on their experience (Hirschman et al., 1983). These doctors deal daily with bleeding and high blood pressure threatening the lives of their patients, but IPV and homicide are often more insidious and thus less likely to come to mind.

Research shows that doctors are more likely to feel efficacious about screening for IPV if they are more prepared, yet fewer than 10% of OBGYNs report receiving education on addressing IPV in pregnancy (Roelens et al., 2009; McCarthy & Bianchi, 2020). Thus, this talk will also arm doctors with actionable steps they can use to implement evidence-based IPV screening into their practice and a procedure for advising patients who screen positively. Deshpande & Lewis-O’Connor (2013) recommend directly asking patients about IPV rather than using questionnaires, so the lecture will discuss how to incorporate IPV screening into the basic prenatal medical history using various strategies. The lecturer will suggest using the Danger Assessment when a patient screens positively for IPV. The Danger Assessment is a set of five evidence-backed questions that accurately identify victims of IPV who are at increased risk of homicide and are thus in the greatest need of resources (Campbell et al., 2009; Snider et al., 2009). From there, the talk will outline resources doctors can offer patients, including information about law enforcement, support groups, hotlines, shelters, and safety planning. The presentation of this protocol for screening and assisting patients who disclose IPV will help doctors become more confident in their ability to address their patient’s needs.

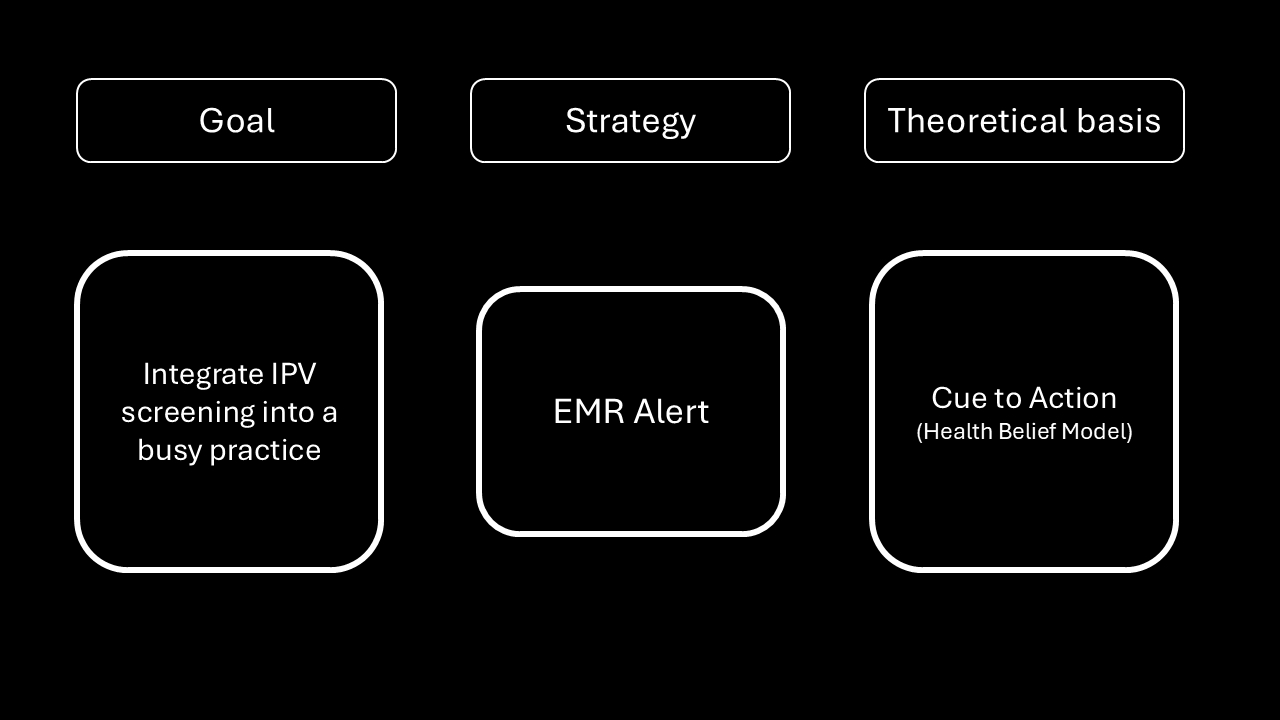

Finally, the presentation will include ways to efficiently integrate IPV into a busy practice. For instance, a widely used method of changing provider behavior is to use an alert in the electronic medical record to remind them to do something in the patient’s room. An EMR alert is an example of a “cue to action” in the Health Belief Model. Such stimuli can lead us to remind us to initiate a health behavior in the moment (National Cancer Institute, 2005). A randomized clinical trial found that an EMR alert increased the screening rate for IPV from 45 to 65% in one practice (Lenert et al., 2024). Integrating this strategy with the information and action plan outlined above will be the most effective way to communicate the underestimated hazard of homicides in pregnant and recently postpartum mothers.

Presentation

References

Campbell, J., Matoff-Stepp, S., Velez, M. L., Cox, H. H., & Laughon, K. (2021). Pregnancy-associated deaths from homicide, suicide, and drug overdose: Review of research and the intersection with intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 30(2), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8875

Campbell, J. C., Webster, D. W., & Glass, N. (2009). The danger assessment: validation of a lethality risk assessment instrument for intimate partner femicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(4), 653–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508317180

Clements, P. T., Holt, K. E., Hasson, C. M., & Fay-Hillier, T. (2011). Enhancing assessment of interpersonal violence (IPV) pregnancy-related homicide risk within nursing curricula. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 7(4), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-3938.2011.01119.x

Deshpande, N. A., & Lewis-O’Connor, A. (2013). Screening for intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 6(3–4), 141–148. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24920977

Gesme, D., & Wiseman, M. (2010). How to implement change in practice. Journal of Oncology Practice, 6(5), 257–259. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.000089

Gunja, M. Z., Gumas, E. D., Masitha, R., & Zephyrin, L. C. (2024). Insights into the U.S. maternal mortality crisis: An international comparison. Commonwealth Fund. https://doi.org/10.26099/CTHN-ST75

Hirschman, E. C., Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (1983). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Journal of Marketing Research, 20(2), 217. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151689

Ibrahim, E., Hamed, N., & Ahmed, L. (2021). Views of primary health care providers of the challenges to screening for intimate partner violence, Egypt. La Revue de Sante de La Mediterranee Orientale [Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal], 27(3), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.20.125

Keegan, G., Hoofnagle, M., Chor, J., Hampton, D., Cone, J., Khan, A., Rowell, S., Plackett, T., Benjamin, A., Bhardwaj, N., Rogers, S. O., Zakrison, T. L., & Cirone, J. M. (2024). State-level analysis of intimate partner violence, abortion access, and peripartum homicide: Call for screening and violence interventions for pregnant patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 238(5), 880–888. https://doi.org/10.1097/XCS.0000000000001019

Lawn, R. B., & Koenen, K. C. (2022). Homicide is a leading cause of death for pregnant women in US. British Medical Journal, 379. https://search.library.stonybr... Central&tab=Everything&query=any%2Ccontains%2Chttps%3A%2F%2Fdoi.org%2F10.1136%2Fbmj.o2499&offset=0

Lee, S., Holden, D., Webb, R., & Ayers, S. (2019). Pregnancy related risk perception in pregnant women, midwives & doctors: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2467-4

Lenert, L., Rheingold, A. A., Simpson, K. N., Scherbakov, D., Aiken, M., Hahn, C., McCauley, J. L., Ennis, N., & Diaz, V. A. (2024). Electronic health record-based screening for intimate partner violence: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 7(8), e2425070. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.25070

McCarthy, J., & Bianchi, A. (2020). Implementation of an intimate partner violence screening program in a university health care clinic. Journal of American College Health, 68(4), 444–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/074484... Cancer Institute. (2005). Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/theory.pdf

O’Campo, P., Kirst, M., Tsamis, C., Chambers, C., & Ahmad, F. (2011). Implementing successful intimate partner violence screening programs in health care settings: evidence generated from a realist-informed systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 72(6), 855–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.019

O’Keefe, D. J. (2002). Persuasion: Theory and Research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. https://books.google.com/books/about/Persuasion.html?id=e3V6Zen0UGwC

Procentese, F., Di Napoli, I., Tuccillo, F., Chiurazzi, A., & Arcidiacono, C. (2019). Healthcare professionals’ perceptions and concerns towards domestic violence during pregnancy in southern Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173087

Roelens, K., Verstraelen, H., & Temmerman, M. (2009). Intimate Partner Violence. The gynaecologist’s perspective. Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn, 1(2), 88–98. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25478074

Roush, K. (2023). Mitigating homicide risk during pregnancy. The American Journal of Nursing, 123(5), 9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000933872.92011.1e

Snider, C., Webster, D., O’Sullivan, C. S., & Campbell, J. (2009). Intimate partner violence: development of a brief risk assessment for the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 16(11), 1208–1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00457.x

Wallace, M. E. (2022). Trends in pregnancy-associated homicide, United States, 2020. American Journal of Public Health, 112(9), 1333–1336. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306937

Wallace, M., Gillispie-Bell, V., Cruz, K., Davis, K., & Vilda, D. (2021). Homicide during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the United States, 2018-2019. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 138(5), 762–769. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004567

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Post a comment